“I’ve always felt a little bit guilty because I was lucky. I’ve been lucky in a lot of things.”

—Donald Trump, in conversation with Roger Ailes, December 1995

It is abundantly clear, nearly ten years since he descended that gold-trimmed escalator, that Donald Trump is the most significant political figure of our time. Even his most bitter enemies would have to admit, however distasteful it may be, that no president has held greater sway over American government other than perhaps Franklin D. Roosevelt during his 12-year presidency, and no single biography has displayed more variety, or taken as many improbable turns, since the rise of Theodore Roosevelt. As the author of this remarkable destiny, Trump himself is chiefly responsible for shaping a story that has altered our politics (many would say for the worse), changed the course of history (in a still undetermined manner), and now places the fate of much of the free world in the hands of a man who, as recently as May 2015, was mostly famous for firing celebrities on a reality show, coiffing his perm-blond hair in an absurd fashion, and going bankrupt in a series of asset devaluations by the end of the 1980s.

But one other individual, previously reduced to a footnote in history, holds the prime responsibility for changing Donald Trump’s fortunes, where a chance meeting in a New York nightclub initiated much of the spooky good fortune one man has experienced for nearly half a century — an unparalleled run of prestige, where astonishing wealth, power, and privilege have been repeatedly balanced by multiple instances of public embarrassment, appalling scandal, financial collapse, and the more recent threats of impeachment, jail time, and even assassination. In retrospect, this opportune encounter a 27-year-old Donald Trump experienced with Roy Cohn inside Le Club in 1973 can be seen as the first act in a complex mentorship that recalls nothing less than the Devil’s bargain embodied in Goethe’s Faust, an exchange of values which remained unapparent, even obscured, for decades (at least to those long familiar with the most public of public figures), but is now seen as the signature influence, the very ink and dye, Trump has used to dominate our politics and write himself into American history.

Having premiered at the Cannes Film Festival to rave reviews (and predictable controversy), Ali Abbasi’s 2024 film, The Apprentice, examines the 13-year relationship Trump formed with Cohn between 1973 and 1986, a period which saw our future president rise from being a virtually unknown son of an outer borough landlord into a national real estate tycoon whose last name would adorn condos, casinos, airlines, hotels, and professional football teams, all before the tender age of 40. Played brilliantly by Jeremy Strong, the Cohn in Abbasi’s Apprentice is every bit as combative, manipulative, and pernicious as the real-life Cohn, a mafia fixer and disgraced judicial strongman who, had he never converged with young Trump in the twilight of his life, would have been dimly remembered for sending Ethel and Julius Rosenberg to the electric chair, and for encouraging the worst of Joseph McCarthy’s demagoguery, as a precocious attorney in the early 1950s. But if Trump, by his own success, has secured Cohn’s place as a permanent fixture in the American memory, then Cohn proffered something far more exceptional to Trump in return — a gift, let us call it, a piece of luck, a talisman that is responsible for the past, present, and future all of us are living through, and this exchange is the theme of both Faust, an iconic 19th century play and dramatic poem, and The Apprentice, a movie that was largely ignored by the public this past winter.

No single figure, not even his father, certainly none of his three wives, let alone anyone in American politics, has been as important to Trump as Cohn, a person described by attorney Joe Klotz as, “One of the most evil presences in our society during my adult life.” Playwright Tony Kushner characterized Cohn as, “One of the worst human beings who ever lived,” after writing the play Angels in America. Cohn’s own cousin David Lloyd Marcus said, “He was the personification of evil,” while journalist Peter Manso described Cohn by turns as “a lawless madman,” “without conscience,” and added, “To call him evil, it’s true, but it doesn’t explain a hundred other things about him.” All this from the phenomenal 2019 HBO documentary: Bully. Coward. Victim. The Story of Roy Cohn.

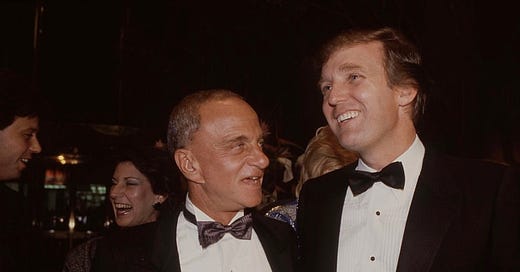

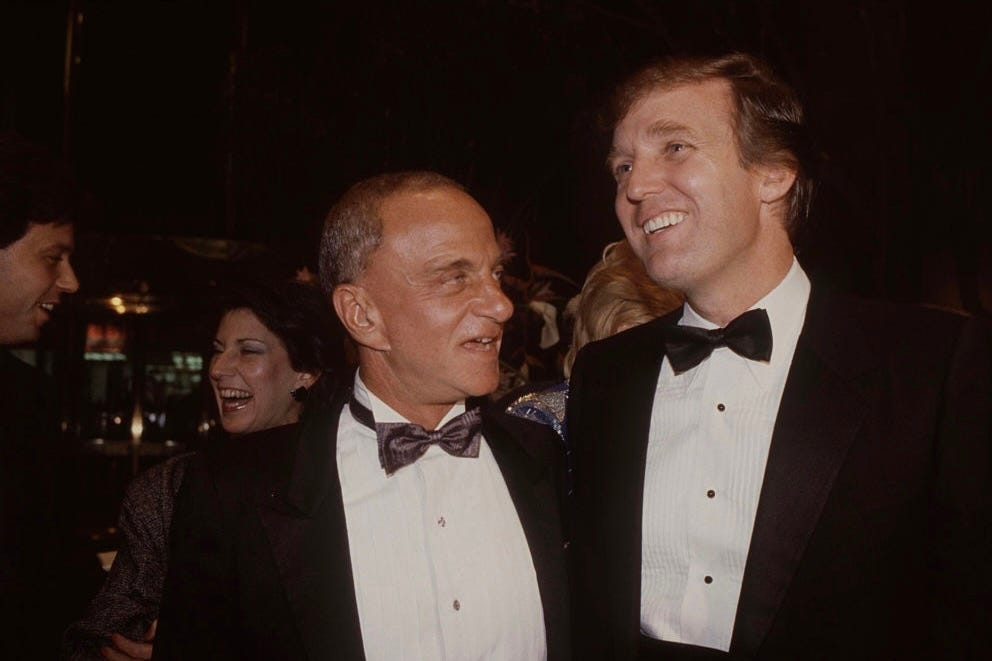

Cohn, in an undated interview before his death in 1986, held up a framed picture of himself and Trump from the latter’s 37th birthday, and recalled, “[Donald] says, ‘Roy is my closest friend.’”

Trump for his part, in a 2016 Washington Post interview, designated Cohn merely as “a really smart guy who liked me and did a great job for me on different things,” but qualified their relationship as no more exceptional than ones he shared with many other attorneys in that period.

Abbasi’s Apprentice tells a far different story, with three scenes that mirror the grand bargain between Goethe’s Faust, a fictional scholar who received everything the world could offer, yet remained unsatisfied, and Mephistopheles, the agent of Lucifer, a cunning, demonic force, who made a bet with God that he could purchase the soul of Faust in return for wealth, fame, power, and all the pleasures of the flesh, even Helen of Troy, before being taken down into Hell, where a long awaited payment could finally be collected.

The first scene that demands our attention occurs about 28 minutes into the film, when a young Trump — played almost perfectly by Sebastian Stan in an Oscar-nominated performance — is initiated by Cohn into the dark arts of power after witnessing blackmail and extortion. Donald (he is not yet Trump, or even Faust, for that matter) sits inside Cohn’s townhome, silent, speechless, unable to process the use of such flagrant immorality. “I don’t know what I just saw,” he mumbles, rationalizing his own complicity as he sits far away from Cohn on the couch, in a lame attempt to remain pure. Cohn orders him to come closer as he prepares the first of many lessons: This is a nation of men, not laws, and men can be bullied, shamed, bribed, threatened, and seduced. “There is no right or wrong,” Cohn tells Donald. “There is no morality, there is no Truth, with a capital T. It’s a fiction, a construct. It is man made. Nothing matters except winning — that’s it.”

The conversation, which pulls the veil from 27-year-old Donald’s eyes over the worthiness of virtue, recalls the admission Mephistopheles makes to Faust upon appearing inside Faust’s study, out of a vaporous cloud, when he introduces his wondrous abilities to God’s once faithful servant: “Let foolish little human souls / delude themselves that they are wholes / I am part of that part, when all began / was all there was / part of Darkness before man / Whence light was born, proud light, which now makes futile war / To wrest from Night, its mother, what before / was hers, her ancient place and space.”

In both cases, while terms of an agreement have been established, a pact requires consecration. Midway through the film, a critical exchange of values between Donald and Cohn is illustrated in a short burst of scenes. Donald stands on the cusp of his breakthrough project, renovating the dilapidated Commodore Hotel in Midtown, having convinced Hyatt’s Jay Pritzker that he has already secured a generous property tax abatement from the City’s Board of Estimate. Of course, this is untrue, so Donald rushes over to his mentor’s home in the middle of the night, frantic, helpless, desperate to secure the greatest favor yet from his patron. “I’ll do anything, whatever you want,” Donald begs. “You can’t turn fishes into loaves,” Cohn replies, about to slam the door on his subject. “I’m begging you, Roy. I believe in this. I’m begging you, Roy, please, just make the call.” Donald is vulnerable and frenzied. His fate lies in Cohn’s hands; only Cohn’s voice — a call to a higher power — can make a difference in his life. Cohn hesitates before telling Donald that he’ll use his influence on the mayor the next morning. “Be glad he owes me,” he nods before they embrace. Donald, near tears, in an uncharacteristic show of gratitude, whispers, “I love you. I love you.”

A complete unknown stands before his benefactor, promising anything he wants in return, so long as this dark force uses his mysterious powers to influence the direction of his life. Have we not seen this before? Is it not unlike the prayer uttered by Faust as he prepares to accept Mephistopheles’ offer, the immortal pact of service, signed in blood, consecrated by power, and paid for in the next life? “Can you provide / a game I can never win / procure a girl whose roving eye / invites the next man, even as I lie / in her embrace? A meteoric fame / that fades as quickly as it came / Show me the fruit before it's plucked / And trees that change their foliage every day!”

Of course, for both Donald and Faust, the foliage of their lives changes rapidly once the exchange is honored. Faust acquires knowledge, love, power, and omnipotence, while Donald enters the stratosphere of the New York elite, constructing a luxury condo-office tower in his own name, marrying a fashion model, fathering three children, turning his image into a national brand of success. Yet, for each man, a debt remains outstanding.

As Abbasi’s film nears its conclusion, Cohn stalks the screen a shell of himself, dying of AIDS, withering under the weight of lies and decades of deception. By now, he’s been disbarred — found guilty of dishonesty, fraud, deceit, and misrepresentation — and is all but abandoned. He appears before Donald like a helpless beggar, demanding to be thanked for his years of service, outraged at the lack of gratitude. “I made you! Don’t you forget that. I made you!” he screams before slapping his mentee across the face. Having little use for him, Donald finally admits a metaphysical truth: “You’ve got some feelings now suddenly? You’re the fucking Devil . . . . You’re no saint, you’re no God.”

The outburst recalls the ending of Faust: Part One, when, after various calamities have driven Faust to despair, despite the summits he has also seen, he casts blame on his benefactor: “So this is what it has come to! This! — Vile treacherous demon, and what you told me nothing! — Yes, stand there, stand there and roll your devilish eyes in fury. Stand there and affront me by your unendurable presence!” Little does Faust know, even in this acrid renunciation, he is merely halfway through his journey; a second half remains, as life has many more gifts awaiting him.

By the time The Apprentice ends, the transference between Cohn/Mephistopheles and Trump/Faust is complete. The Bully-Coward-Victim of McCarthyism is dead, but he lives on inside his student, who stands at the height of his powers — or at least the first of several heights he will reach. Looking out from the 58th floor of his personal skyscraper, 40-year-old Donald quotes his mentor’s “three rules of winning,” thereby making them his own. He is no longer Donald, or even Trump; only Faust is the appropriate designation for the rewards that lie ahead.

In the final shot of Abbasi’s two-hour film, the American flag flutters in the eyes of a man lost in thought, murmuring to himself his own abilities, closing with the words, “You have to have it.”

And after all of this, what does he have?

More than most men can hope to dream.

A hotel and condo tower in Manhattan are not nearly enough. Over the next few years, long after the credits roll and we transition from film into reality, our American Faust will purchase three Atlantic City casinos, a USFL football team, an airline, a 281-foot superyacht, the Plaza Hotel, a 20,000 square-foot mansion in Connecticut, and the historic Palm Beach residence of Mar-a-Lago. Not to be outdone, he will also leverage his fame to host WrestleMania IV and V, the Tour de Trump bicycle race, and several championship boxing fights. He’ll publish a bestselling memoir, appear on Oprah, and even create a board game in his own image.

What more could a boy from Queens want?

Perhaps the real question should be: What type of life is this?

But this is the point of the pact. Nothing is ever enough for the American Faust.

Even sudden reversals of fortune cannot stop or temper him. How do we explain the psychology of a man who endures divorce, becomes the butt of late-night talk shows, succumbs to the indignity of Pizza Hut commercials, and finds his net worth at negative $957 million? Clearly it is an individual agnostic to any reality outside his own ego, whose belief in his own resilience is buttressed by his reputation as the nation’s best-known businessman, as well as the power of positive thinking learned firsthand from his childhood minister, Norman Vincent Peale. By his 50th birthday, June 1996, Faust, using guile, charm, bluster, lies, and, yes, luck, negotiates himself out of a personal financial crisis, appeases every creditor, issues his own stock, and finds new life in what one former critic, analyst Marvin Roffman, calls “a classic” financial turnaround, which “ought to go, if it isn’t in there already, into a Harvard Business School textbook.”

And yet, by the time the century closes, in the autumn of 1999, Faust already recognizes what he needs to fill his insatiable soul, for money is no longer enough, and the Miss America Pageant, which he owns, is merely a delicious toy. He appears on Meet the Press with Tim Russert, to discuss his intentions to seek the presidency. There he sits, soft spoken, fidgety, uncommonly nervous. He describes Republicans as “just too crazy right,” and positions himself as “very pro-choice.” Eventually, he’ll decide against running, shrewdly realizing a third-party bid stands no chance of winning the presidency at the pinnacle of empire.

But if true power, ultimate power, remains 16 years away, there is still one more gift waiting in the wings for our American Faust, an experience that includes both money and power but transcends them into something far more enduring: adulation.

In January 2004, Faust secures a deal with NBC to appear on a weekly TV show. The opening credits will ask each viewer — 20 million a week for 14 seasons — “What if you could have it all?” before inaugurating a game of elimination where the losers are humiliated and the lone victor, an average Joe, earns the opportunity to work for Faust and his children. Week after week, for more than a decade, citizens of the republic tune into a fantasy made for Faust, by Faust, and about Faust, a production that displays his properties, showcases his strength, touts his talents, and sells his carefully choreographed image as the epitome of success to a 21st-century audience already struggling to separate reality from television, a people who will soon be unable to distinguish truth from lies, but are being prepared, maybe even conditioned, to admire the man who has it all, whose very life is the promise of achievement.

Despite this newfound adulation, there is even more Faust must achieve to honor the exchange made in 1973.

By the time he vanquishes two political dynasties and raises his hand before God and the Capitol as one of 44 men to take the highest oath of office, Faust would appear to have reached his apex, or at least to have satisfied an insatiable appetite with the trappings of presidential power and the wonders of the White House. But not even state dinners or State of the Union speeches are enough. An election is held amidst a once-in-a-century pandemic and the people cast him out resoundingly. Facing a reversal of fortune for the first time in decades, Faust panics. He becomes the first president in 244 years who refuses to concede defeat; he violates his oath, pressuring public servants, spreading lies, sowing division, all while plotting to stay in power — these moves culminate in a deadly assault on the legislature as it attempts to certify the vote for his opponent. Faust leaves office in disgrace, certainly finished, preparing to finally admit to the spiritual Mephistopheles, long dead but always present, haunting his memories as an invisible mentor, that he’s effectively satisfied. Faust tells a cheering crowd before he boards a plane to Palm Beach: “We’ll be back in some form . . . have a nice life.”

And yet this life, by nature of the exchange, is not yet done. In fact, not even death appears capable of laying it to rest; immortality, in the age of AI, seems far more likely. The coronavirus was no match; an assassin’s bullet missed the iconic blond head by a millimeter; old age is ostensibly helpless to tame his energies. And so, at 78-years-old, he begins the third and final act, a second term as president, as a changed Faust, an angry Faust, a chosen figure determined to play the role of revolutionary, conqueror, Caesar, all in one. He will lord over an outdated order and destroy a corrupt establishment, carrying within him the potential to become some sort of God to the followers of his bizarre secular religion.

And this is how it is and had to be. For a man who has tasted the pleasures of gold and flesh, who has reveled in the bounties of fame and fortune, somehow, someway, not even the entire United States is enough to satisfy his desires — because he made a deal a long time ago, half a century to be precise, and we’re the ones fated to discover whether Mephistopheles will still collect his payment, long overdue by now, with the Constitution signed as the receipt.

Brian Pascus is a writer and journalist in New York City. His financial journalism can be found at Commercial Observer.

Trump would be a half forgotten foot note if the republican leadership had honored their oath to the constitution and acted in the nation's interest by impeaching him after Jan 6.

After watching this film I thought of Macbeth, but Faust is even

better- perceptive analysis