Oscar night is upon us! Who’s going to take Best Picture? A top contender, of course, is The Brutalist, and we’re deeply excited to have the writer and artist Megan Gafford in The Metropolitan Review meditating on the film and what it means from an architectural perspective. What is—or was—Brutalism? Why does it still matter? Gafford wrestles with these questions in remarkable fashion. As always, if you find yourself becoming a bit of a TMR junkie, please pledge $50 for the year or $5 per month to help us get to a point of genuine sustainability. We can’t do it without you!

-The Editors

I wonder if László Tóth escaped the Nazis by jumping out of a prison transport train? Director Brady Corbet does not tell us how Tóth, a fictional Hungarian Jewish émigré in America, survived the Holocaust in his epic The Brutalist. But towards the beginning of the film, Tóth mentions that he broke his nose jumping from a train car, while mistaking as gunfire the sound of bone cracking against a tree.

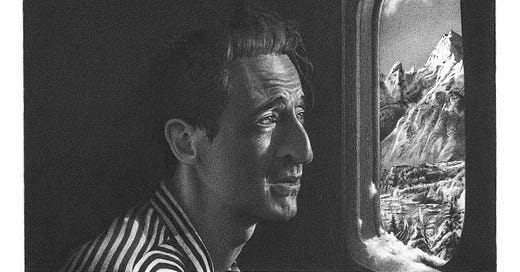

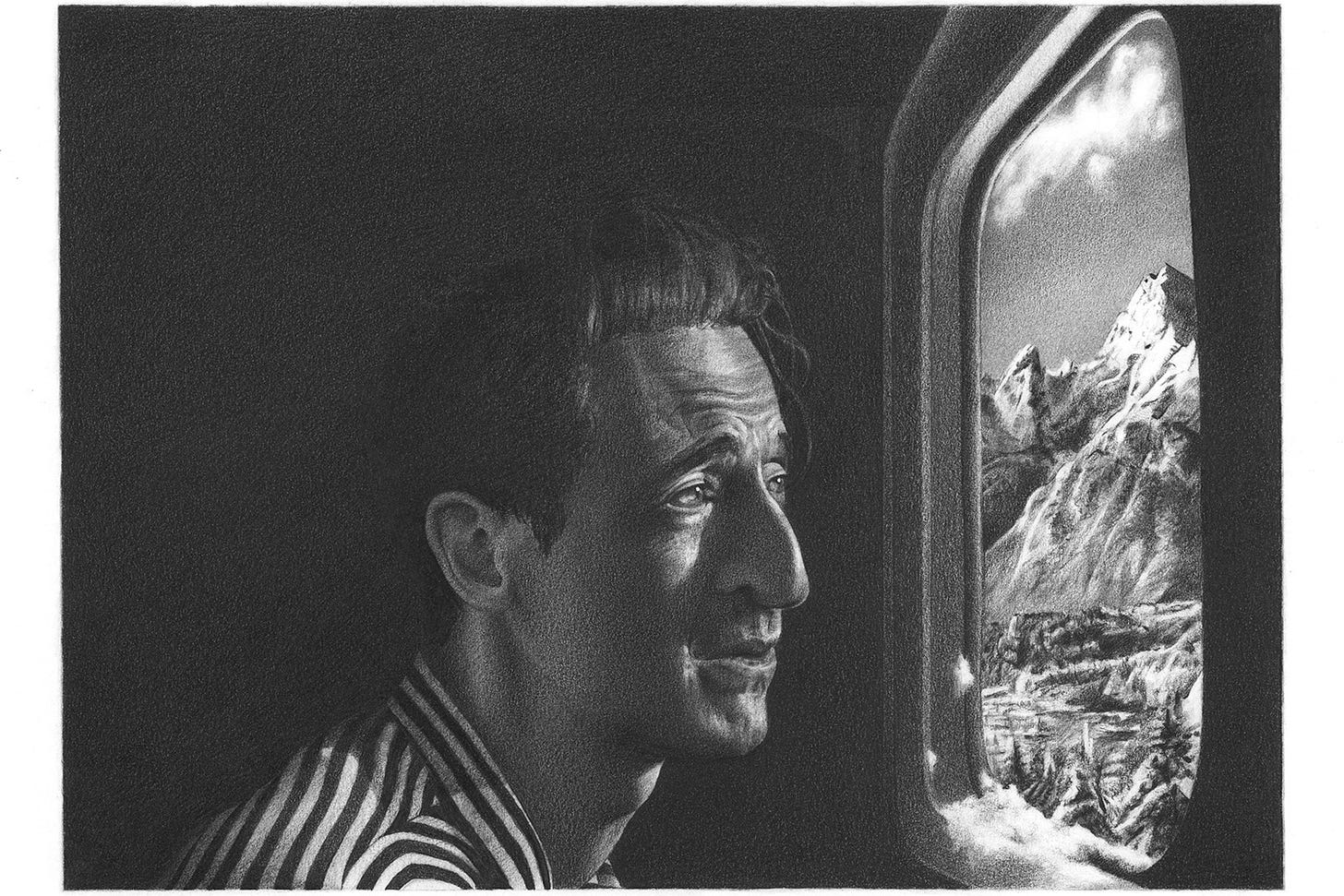

Perhaps Tóth, as an architect and aesthete, would appreciate how Auschwitz survivor Viktor Frankl described a trip in a Nazi prison train as a rare opportunity to experience beauty:

As the inner life of the prisoner tended to become more intense, he also experienced the beauty of art and nature as never before. Under their influence he sometimes even forgot his own frightful circumstances. If someone had seen our faces on the journey from Auschwitz to a Bavarian camp as we beheld the mountains of Salzburg with their summits glowing in the sunset, through the little barred windows of the prison carriage, he would never have believed that those were the faces of men who had given up all hope of life and liberty. Despite that factor — or maybe because of it — we were carried away by nature’s beauty, which we had missed for so long.

Maybe on Corbet’s cutting room floor, there’s a scene where Tóth got lucky, and the bars on his train car window broke off during the journey. The wispy man would have been slender enough to launch himself out of a small opening, once the train slowed just enough to risk it. Even if the attempt killed him, at least he would die on an awesome mountainside instead of inside the next camp.

But Tóth jumped out of the frying pan and into the fire. Corbet barrages us with so much trauma throughout the film — adultery, poverty, betrayal, famine, rape, addiction, young children losing their mothers, disease, more rape, overdose, suicide, the woman who became mute because her pain was unspeakable — that including the Holocaust on screen would have been gratuitous. As historical backdrop, it merely hovers behind the story until the epilogue, when Tóth’s life’s work is celebrated at the 1980 Venice Biennale of Architecture. Then we learn that the layout of the monumental Brutalist building that Tóth designs and builds throughout the film is based on his prison in the Buchenwald concentration camp, but with a twist — he gives the cramped rooms high ceilings meant to inspire hope.

Tóth is modeled on architects like Marcel Breuer, a real Hungarian Jewish immigrant who helped bring Modern architecture, including Brutalism, to America. The Modernists scrubbed off architectural ornamentation in search of “honest" structures: austere, pared down shapes made out of modern materials like steel, sheet glass, and reinforced concrete. For Le Corbusier, the father of Modern architecture who abhorred applied decoration as tainting pure form, “A house is a machine to live in.”

When Reyner Banham became the first critic to try to define the Brutalist style of Modern architecture in 1955, his starting point was Le Corbusier's declaration that “Architecture is, with raw materials, establishing moving connections.” Banham observed that “Whatever has been said about honest use of materials, most modern buildings appear to be made of whitewash or patent glazing, even when they are made of concrete or steel.” It does not bother Banham that the Modernists confused honesty with being literal, only that they had not taken the form of their buildings literally enough — until Brutalism, which fulfills Modernism's promise because it “appears to be made out of glass, brick, steel and concrete, and is in fact made of glass, brick, steel and concrete.” Le Corbusier so admired the versatility of le béton brut — “raw concrete” — that the French phrase morphed into the name of this architectural style that uses it with gusto. Breuer and other Brutalist architects built on Le Corbusier's legacy by turning concrete into an aesthetic unto itself.

Brutalism also unearths an underrated, and perhaps surprising, influence on Modern architecture: German Expressionism. Breuer’s mentor Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus school attended by both Breuer and the fictional Tóth, admired Expressionist architects like Erich Mendelsohn. Another Bauhaus architect, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, was designing Expressionist buildings in the early 1920s before helping pioneer Modern architecture. When Mendelsohn built the Einstein Tower in 1924 for astrophysicists making observations that could test Einstein's relativity theory, he used concrete to fashion smooth, gentle curves, like an Art Nouveau building in the nude. There is no applied decoration, but the shape of the building itself is ornamental.

Similarly, some Brutalist buildings come in flamboyant forms, especially those built once the movement had matured around 1970, such as the Geisel Library, a concrete and glass diamond perched on San Diego like a shining solitaire ring. But even at the beginning, pioneers of the style pushed back against overly formalist interpretations, as when the early Brutalist architects Alison and Peter Smithson complained that “Up to now Brutalism has been discussed stylistically, whereas its essence is ethical.” They describe their ethics in the spirit of Edvard Munch musing that art is the outcome of dissatisfaction with life:

Any discussion of Brutalism will miss the point if it does not take into account Brutalism's attempt to be objective about “reality” — the cultural objectives of society, its urges, and so on. Brutalism tries to face up to a mass-production society, and drag a rough poetry out of the confused and powerful forces which are at work.

Though Corbet sets aside real architectural history in The Brutalist, he channels this undercurrent of Expressionism that emerged in real Brutalist architecture. Unlike the happy stories of real-life architects such as Breuer, who escaped Europe before it was too late and then went on to enjoy a cushy position on faculty at Harvard, Tóth is a maximally tragic figure who got a job shoveling coal in Philadelphia while shooting up heroin in the basement of a homeless shelter. The film mostly ignores Modernist ideas about architectural formalism, so that when someone tries to modify Tóth’s building design, he is not enraged because his honest forms have been marred by decorative pastiche, but because the modifications would have lowered the high ceilings that were central to the emotional thrust of Tóth's vision.

He wanted to co-opt the cramped layout of a concentration camp so that he could transform it — conquer it — with the addition of an uplifting, airy expanse above, like keeping a slice of Heaven in an opaque terrarium. So when a couple philistines tried to shave some height off his building to save money on construction, Tóth demands that his own salary be used to pay for the cost of building higher, ensuring that both his artistry and poverty continue. For without the high ceilings, Tóth felt he would essentially recreate his torture chamber.

The shape of his building has little to do with the beauty of a cube, which Tóth briefly praises in the one instance when The Brutalist hints at the sort of formalist ideas found in Le Corbusier’s manifesto. But the shape of Tóth’s building has everything to do with the way this persecuted man views reality, just as the pioneers of Brutalist architecture demanded. By raising the height of his ceilings, Tóth attempted to drag a rough poetry out of the shape of the Buchenwald concentration camp.

The result is imposing, which is true to the way that real-life Brutalist buildings aspire to be monumental. Breuer's most famous contribution to the genre is the old Whitney Museum building on Manhattan's Upper East Side. The Breuer Building looks as if an irate giant slammed down a boulder to flatten some pre-war Beaux-Arts luxury tower with a hulking mass fresh from the quarry. It features upside-down setbacks — in 1916, New York City began requiring that the upper floors of skyscrapers be “set back" to allow more light to reach the street, giving tall buildings a series of terraces as the upper levels become skinnier than the floors below — so that the squat Breuer Building hunches over the sidewalk to cool pedestrians with its shadow. Its façade has fewer windows than a prison, which protrude from the smooth, gray walls at random, like a small scattering of sharpened crystals growing on a rock.

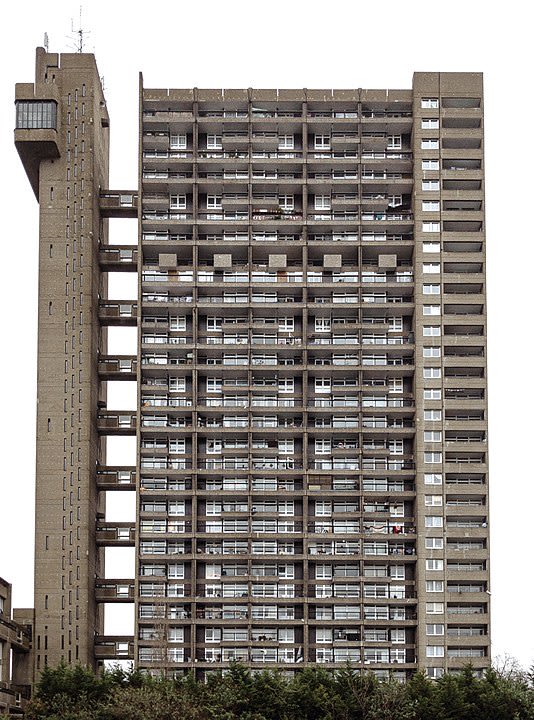

Brutalism feels brutal to most people who look at it. Ian Fleming hated it enough to name a James Bond villain after another Hungarian architect, Ernő Goldfinger, whose Trellick Tower in London features in the dystopian Black Mirror movie. Most likely, the style will never escape the perception that it was named for its effect. That it initially developed in the literal rubble of bombed-out London after a ghastly war only reinforces the assumption that Brutalism is a grim expression of pain. People with some knowledge of architectural history are quick to point out that Brutalism is not named after brutality — it is considered a coincidence that translating “raw concrete” from the French le béton brut happens to describe the style’s effect so well — but The Brutalist wrests control of the narrative away from highfalutin theorists once and for all, who would explain the style as a formalist pursuit of honest materials, and instead cements the myth of Brutalism as an expression of brutality.

Though sticklers resent how the film overrides much history, they fail to appreciate that The Brutalist as myth is more useful than a biopic for appreciating this architectural style. Until now, Brutalism has been a tragedy without a hero. No actual Brutalist architect has suffered enough to earn the right to bludgeon Madison Avenue.

But László Tóth suffers beautifully. When actor Adrien Brody knits his mournful eyebrows together, it is as if Arachne herself has woven a tapestry of torment into Tóth’s forehead. The Brutalist would be nothing without Brody, who has a face rivaling the man in Munch’s The Scream for its emotive range — whose famous grimace is mimicked offhandedly by another character in the film, during a picnic scene that takes place right after Corbet hints that Tóth’s niece has been raped.

Brutalism only makes sense through a tragic hero, for without such a figure to do the expressing, the art form is illegitimate. An aesthetic that brutalizes passersby is unforgivable unless, at the very least, someone felt that pain before inflicting it on others under the guise of artistic expression. So while the real Marcel Breuer is insufficient, the endless trauma engulfing László Tóth might justify all manner of secondhand suffering.

And so with Brody's performance of the tortured artist, The Brutalist tries to vindicate an architectural tradition.

But, our hero misinterpreted his own design. For what is a concentration camp with higher walls, if not a more effective prison? Tóth unwittingly reinforced the cage he tried to transcend — and so failed to drag rough poetry out of reality.

Now his failure has become the myth of Brutalism.

Megan Gafford is an artist and writer based in New York City. She publishes visual essays at Fashionably Late Takes.

Thank you for the education in Brutalism. I grew up around the corner from the Bruer and still live near by and pass it often. I HATE it. As a child, it scared me to look at it. I didn't know why, it just did.

Great essay. My guide to the Holocaust is Primo Levi and I'm pretty sure he would have contempt for a movie about an architect modeling a building on a camp (or lager).

So many elements to this film!!! I am a furniture maker and probably could write a review focusing on the furniture… and by the way I really appreciated the architectural history.