There aren’t many novelists and thinkers out there like ARX-Han, who operates on the cutting edge of twenty-first century literature. Today, he writes on a popular novel from last year that attracted a great amount of discussion, particularly around the role of disaffected men in literature. (By the way, Han’s novel, Incel, shouldn’t be missed.) We’ve been humming over at The Metropolitan Review, producing reviews and essays for you at the clip of the Eagles Super Bowl pass rush. Please consider pledging $50 so we can keep the momentum going and get our print issue out the doors. We need you!

-The Editors

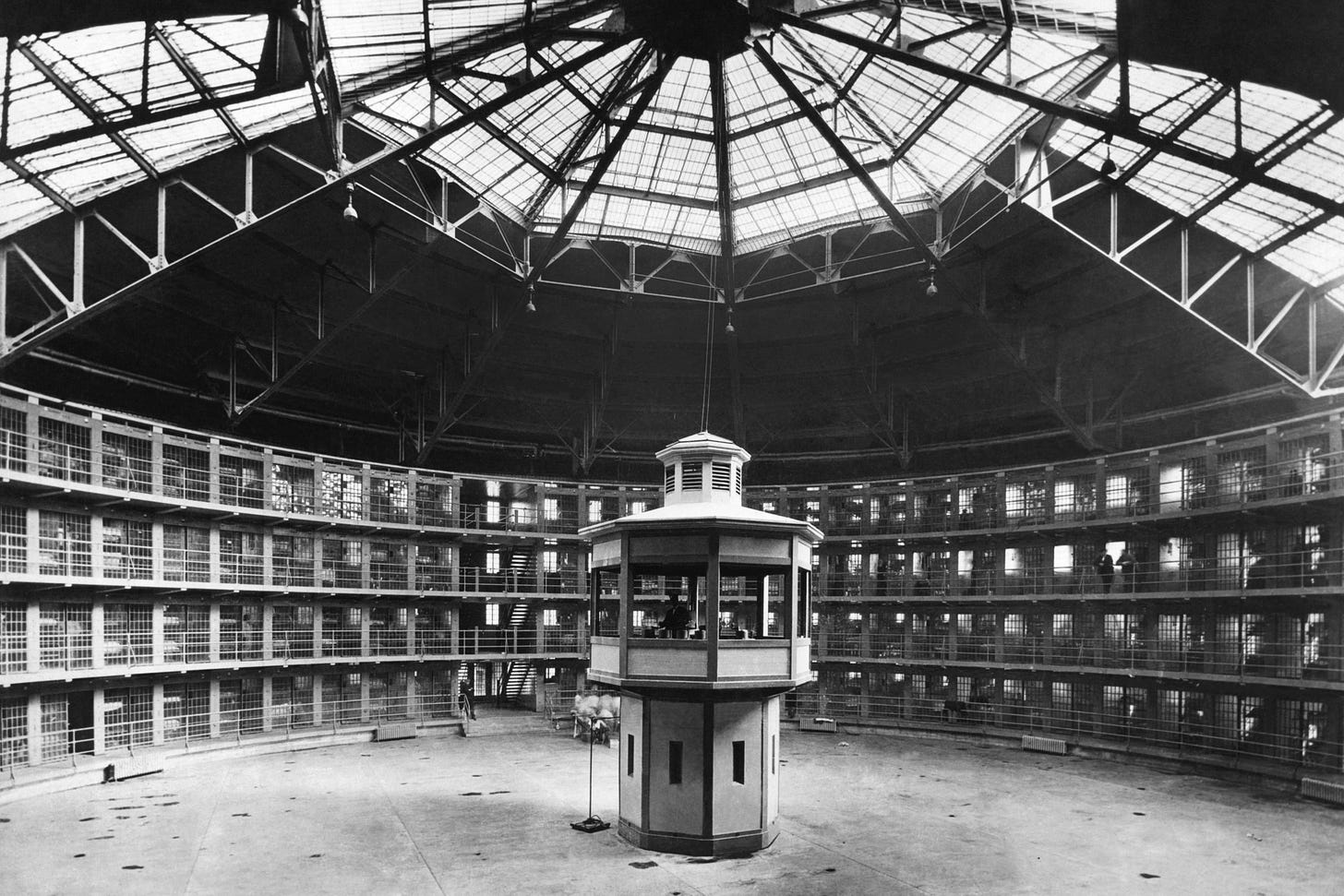

What do you need to build a panopticon?

If you ask the ghost of Jeremy Bentham, who originated the concept in the late 18th century, he’d say something like the following: you need a circular building with a central observation tower staffed by a single guard. You need the ring of the building to be built with cells filled with prisoners who are being observed by the guard in the tower.

If you ask the contemporary liberal subject — the citizen of a free society — you’d receive a more complicated answer. The modern concept of a panopticon isn’t confined to a single building, but expands into the more sprawling, networked, and technologically sophisticated notion of the authoritarian surveillance state.

But what if we were to strip these definitions of their material aspects and simplify the concept as much as possible?

In so doing, we’d arrive at something simpler. We could imagine the minimalist version of the panopticon, one that does not require any technology: a small group of prisoners seated in a circle, with one guard seated in the middle.

Indeed, you could simplify this even further: you could remove the person in the middle, turning each person into both a prisoner and a guard.

The result would be something like a circular firing squad: a decentralized, peer-to-peer panopticon in which each person surveils and punishes the others for transgressing against the group’s norms.

Dear reader: do you read — or write — fiction?

If so, does this concept sound familiar to you?

Is it because I just described the structure of a creative writing group?

Playing to Win vs. Playing to Not Lose

Tony Tulathimutte is the product of the modern, professionalized university system that has produced our current cohort of elite literary fiction writers in America.

As a young man, he won a prestigious Whiting Award and graduated from the (even more) prestigious Iowa MFA workshop. Following this, he went on to put out one of the best voice-of-a-generation millennial novels in his excellent Private Citizens, a work that holds up exceedingly well quite a few years later.

For a number of years, he has also successfully led CRIT, an independent writer’s workshop that mirrors the structure of the group-based MFA, recapitulating the same system of peer-driven feedback that (presumably) helped to guide his own development as an author of fiction.1

The best framing for understanding Tulathimutte, then, is that he's a highly talented writer who's spent his formative years as a writer progressing through a sequence of institutional or institution-adjacent social panopticons (“prestigious writers’ groups”).

While many good works have nonetheless emerged out of this system, these circular filters have the tendency to flatten and homogenize literary works by punishing writers who have contaminated their stories with sharp, problematic edges that diverge from the consensus view on any number of socially inflammatory topics.

Think of the publishing pathway for these elite writers as a sequence of checkpoints or purity filters — in order to make it to the end (and publish your book), a manuscript has to be repeatedly cleared of any problematic narrative contaminants.

Writers like Erik Hoel have shrewdly noted that this perpetuates an intrinsically defensive posture, directly incentivizing writers to minimize the “attack surface” of their novels.2

Tulathimutte’s latest book of interconnected short stories is woven around the central theme of rejection—and, by extension, tackles the thorny subject of modern inceldom in both its male and female varieties.

Also salient is his personal Twitter account, which is typically composed of shitposting hilarious one-liners and sometimes includes self-deprecating jokes about his dating life. Years ago, he did an interview with Brad Listi where he spoke frankly about the social difficulties of growing up as an Asian male in America.

All of this is to say that Tulathimutte’s position is both well-established and deeply risky: it’s because he is so established that he is particularly vulnerable.

As (comparatively) mild as the narrative expressions of inceldom in Rejection are, we are only several years removed from peak Twitter-mob literary cancellations. Whether because of his maleness or because of his Twitter timeline, one must infer that he certainly recognized the potentially radioactive identitarian connotations of writing a novel like this.

Thus, the confluence of his talent and his restrictions produced something like the expected result: Rejection is at once brilliant and deeply frustrating. To really understand why it’s so uneven, you need to read the last chapter first and work your way backward, examining the things that he doesn't talk about so that you can place the author’s selective attention in context.

First: the ending.

It’s a brief, autofictional device that I’ve yet to see deployed in modern literary fiction: a pre-emptive autocancellation. It's the skeleton key to, in equal measure, understanding the book's strengths and weaknesses.

The chapter in question, titled “RE: REJECTION,” takes the form of a rejection letter from a prospective publisher who has declined to publish the book. In the opening section of the letter, Tulathimutte anticipates the argument you might find in the kind of Twitter thread that could conceivably be weaponized against him:

We found much to enjoy in the spiraling dissections of the characters’ psyches, and most work well enough as standalone fiction (though too long for most publications). But the further we read, the more we sensed an evasiveness to the book that grew harder to ignore. We assume the topic wasn’t chosen at random, so the book’s existence and lengthy gestation implies a personal investment, yet you seem to take every opportunity to disavow it, putting yourself at a defensive remove that ultimately left us cold and unsatisfied.

This autocancellation soon escalates further:

Viewed less charitably, it could be read as a way to head off certain dreaded allegations of self-pity and navel-gazing; an attempt at misdirection, as you smuggle your own hang-ups into theirs, while scoring brownie points for imaginative empathy. However, we believe that these distancing attempts only end up drawing attention to you, in a way that feels embarrassingly unintentional.

An unsophisticated writer would use a trigger warning and emphasize the rhetorical defense of having used a sensitivity reader.

Because Tulathimutte is a sophisticated writer, he does something cleverer than that, breaking the fourth wall by simulating his own literary cancellation to pre-emptively sap the emotional activation energy required to assemble a Twitter mob that might be his ultimate undoing.

In a way, it’s an absolutely brilliant form of evasion.

But it’s still an evasion rather than a confrontation.

When we read literary fiction, as readers, the thing we are fundamentally looking for is a confrontation with the (artistic) truth — in all its pain and glory.

Thus, the central tension of Rejection is the frisson of writing about the transgressive topic of modern inceldom while dancing with the personal risk of literary cancellation in the age of the peer-to-peer panopticon. Because each story’s particular narrative trajectory is located at varying degrees of proximity to the nuclear topic of “realistic depiction of the sexless, angry young man,” the stories vary wildly in quality.

In effect, Tulathimutte reads like a writer possessed with unlimited amounts of cleverness working under the social constraints of his social milieu. He writes like an extremely talented writer who isn’t playing to win, but playing to not lose.

Where a story doesn't directly interface with statistically problematic topics, he reaches great heights because he doesn’t have to compromise on artistic honesty.

“Pics” is by far the standout story in the collection.

It’s about a young woman’s spiraling descent into an increasingly self-destructive loop of compounding romantic and personal disasters, an unfortunate series of events initiated by her spontaneous entry into a completely understandable, no-win trap of a casual situationship with a longtime friend that soul-wreckingly punctures her expectations almost immediately after-the-fact:

In the uber she gets lipstick on her knuckles as she tamps mac and cheese into her mouth. What spooked him? What's wrong with leaving things open-ended, why'd he shut it down so decisively? She did *not* even come on that strong. It feels pointlessly penalizing that he won't even go for casual sex when she's totally down for it, she can handle it: that's all she's ever handled. Apparently she's not hot enough to fuck twice, but their friendship meant little enough to risk fucking once.

This initial, post-hookup rejection rapidly escalates into a searingly painful instance of intrasexual white-woman/Asian-woman competition. Here Tulathimutte gets a taste of transgression, flirting with a topic that’s rarely discussed. The white protagonist, Alison, finds herself in competition with a thinner and more attractive Korean woman, Cece, who sports “six inches of visible midriff exuding supreme torso confidence.”

(Rejection is littered with clever, inventive moments like this, things that could only work in the context of the literary medium's capacity for capturing stream-of-consciousness.)

Throughout “Pics,” Tulathimutte’s command of style, metaphor, voice, characterization, pacing, description — everything, frankly — absolutely shines through. But it succeeds, in part, because the particular trajectory of this character's femceldom averts the truly radioactive blast radius of its asymmetrical male counterpart.

The collection's male analog to “Pics” is the well-known and well-regarded story “The Feminist,” an exceedingly clever (and hilarious) tale about a young incel that went viral when it was published in n+1.

The strength of ‘The Feminist” lies in the way that Tulathimutte balances the depiction of male inceldom with a running gag about the protagonist’s increasingly complex verbal and psychological social-compliance strategies that inevitably results in the problems you get from stacking too many layers of neurotic metacognition.

Initially, when I read “The Feminist,” I was deeply impressed by its cleverness, but upon re-visiting the story for this collection, I find myself feeling that cleverness is a substitute for frankness. The bare metal of male interiority — of male incel interiority — is simply not something that an institutionally-established writer like Tulathimutte can guide through the serial checkpoints of the traditional publishing and MFA-world.

It’s just too ugly, too toxic, and too dangerous.

For a collection that has been hailed as the definitive novel about the subject, this ultimately means that, “Pics” aside, most of the stories generally have very little to say. As entertaining and well-crafted as it is, “The Feminist” reads like an extended joke that terminates in a completely caricatured depiction of incel radicalization. That’s fine on its own terms, but my intuition is that this was still a form of artistic compromise in lieu of engaging with the more brutal elements of contemporary male psychology.

Sadly, the remainder of the collection does not approach the strength of the first two stories. “Ahegao” is a story about sexual shame that evades a realistic depiction of any existing paraphilias by substituting in an instance of over-the-top absurdity. “Our Dope Future” presents a milquetoast critique of Silicon Valley narcissism when it could have addressed something substantive like the Valley’s enthusiastic integration with the military-industrial complex or its current race toward potentially-species-ending Artificial Superintelligence. “Main Character” contains one hilarious scene of turn-based rhetorical combat in a college dorm that ultimately fades out into another one of those pseudo-thinkpieces about the internet and identity (we’ve read many of these before!).

As I made my way from the strong opening to the diminutive ending of Rejection, I found myself wishing for an alternative world where Tulathimutte would do something that I would never have the courage to do — to break out of his peer-to-peer panopticon and immolate his entire social and professional network in the pursuit of truly generational literary greatness.

Can he do it one day?

Personally, I have to say that I believe in him.

ARX-HAN is the author of the novel Incel and writes the Substack newsletter DECENTRALIZED FICTION.

Is “the literary establishment is corrupt” as a framing for a review a house requirement or recommendation for The Metropolitan Review, or is it just a coincidence that quite a few of the offerings so far use this? As a reader who is rooting for the success of a new venture in books and literary criticism, I can say it is has already become incredibly tiresome, even when I might agree with the structural critique.

Wow. What a great piece. Thanks for this.