It Wasn't Real, But It Was Beautiful

On the WWE Holiday Tour Live and Gabe Habash's 'Stephen Florida'

Does it matter if wrestling is real? What kind of beauty lies in the make-believe? Olivia Cheng is here for The Metropolitan Review mediating, in moving fashion, on this all-American pastime and how it intersects with these greater questions about what it means to be alive. If you like this essay and have been a regular TMR reader—there are a lot of you now—please pledge $50 for the year so we can sustain ourselves indefinitely and get this big beautiful print issue to the printer.

-The Editors

Last year, on the day after Christmas, I went alone to the WWE Holiday Tour Live at Madison Square Garden, where I sat in nosebleed seats. I wore a plaid button-down shirt and black jeans. I listened to “Danza Kuduro” on repeat on the half-hour walk from my apartment.

My life was stable for the first time in two years. I was twenty-nine, living in New York after a nearly ten year hiatus, and dating a wonderful medical student at the University of Michigan who loved me very much. Everything was good. But I hadn’t finished writing my book and editors often edged me on whether my short stories would make it into their magazines (Not this story, but maybe the next one? Keep submitting to us!). I loved the medical student, but sometimes worried about our relationship. We never fought! Was that good? Or did it hint at some pliability of his that was a weakness of character? Back in New York, I felt like an animal free for the first time. I wanted to see men pound each other on the aptly named Boxing Day.

The last and only time I went to a wrestling match was in Mexico City where I went with my ex to see Lucha Libre. I was twenty-four and convinced he was the one. He grew up in Connecticut, went to Choate and then Yale, and spent summers in Tiverton. I loved him more than I had ever loved anybody, but my prefrontal cortex hadn’t fully developed yet. We broke up after five years together when I chose to go to Michigan for my MFA rather than stay with him in California. Although he had already retired on his vast Databricks stock, he wouldn’t move with me.

But things had been complicated with him from the start. He needed to wake up at the same time every day and eat the same cheesy bagel every morning. He needed to go to HIIT class at least twice a week and drink alcohol no more than three times a week. If we deviated from the rules, he became upset and frustrated. He didn’t like to listen. I had always had a certain affection for men with a touch of ‘tism, but as the years passed by, I found his uncompromising plans at odds with my own desires.

I felt like a snob when I sat in my seat and opened my notebook. My limbs felt stiff and mechanical. Even though I had been looking forward to the WWE Holiday Live Tour for weeks, the notebook felt like my only justification for being here. Everyone else was with their friends and families, dressed in wrestling paraphernalia.

The garden smelled of hot dogs and farts. A single ring sat in the center of the stadium. Fans wore the colors and makeup of their favorite wrestler. Parents came with their children. Adults wore full costumes adorned with championship belts. Fans’ dedication to their favorite wrestlers’ fashion was reminiscent of Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour. I have never seen so many grown men in leggings except perhaps at my high school’s production of Chicago. The girl behind me was dressed in the t-shirt of her favorite performer, Damian Priest, and wore heavy purple eyeshadow on her lids. When I asked her what she loved about WWE, she said, “The drama of it all. It’s a soap opera and it’s never-ending.”

I thought of the only wrestling book I had ever read, Stephen Florida by Gabe Habash, published by Coffee House Press. Stephen Florida follows a young man through the college wrestling circuit in North Dakota. In the novel, Stephen’s life (and mind) descends into chaos during his final year wrestling after an injury: “It is psychologically healthy every now and then to experience something you don’t tell anyone, that you don’t let out for any reason, that’s only yours.”

Although different from the glitz and glamour of WWE, I’m reminded that all sports, from cheerleading to tennis, rely on some level of buy-in. The performers of WWE buy into their characters’ schtick. To Stephen, the only thing that’s real is the mat. Everything else crumbles around him. Despite never having had his face pressed against the mat himself, Habash skillfully dissects what makes certain athletes great and others simply good: “Identity is curious and always getting misplaced, sometimes you have to hold it pretty hard to keep it from getting away. I was never once the most talented, not even close, but I always had my single-mindedness, foolish greedy dodo single-mindedness.”

I didn’t want to think about WWE with a tongue-in-cheek sneer. I wanted to engage in the obsessive, dodo-mentality that compelled these performers to give and take punches to the face — and compelled thousands of fans to keep watching.

When the holiday show began, lights flashed everywhere, LA Knight emerged in front of a yellow and orange screen with the word “YEAH!” bouncing up and down. Running to every corner of the ring, he was fully oiled up and his prominent abs hinted at dehydration. I closed my notebook. The show was starting. I was ready.

I am somebody who has to stop herself from taking things too far. I’ll make jokes about cannibalism or 9/11 in socially inappropriate times. I’ll laugh at the wrong moments. I’ll make my eager feelings too clear at the end of a first date. I have learned to hold back over the years. Still, I am the furthest thing from the wispy, mysterious art girl of today’s Dimes Square culture. A male literary agent once told me, “you’re hot, but not in the right way.”

At the WWE Holiday Tour Live, I shed my outer (and inner) snob, and screamed “Pussy!” at Dominik Mysterio for slipping beneath the ropes, and laughed outrageously loudly at CM Punk coming into the steel cage in a towel. Wrestlers were dressed to the nines with skimpy outfits and shiny bodies — The New Day clad in fuzzy robes, and Gunther in his boots and tiny Speedo. I felt particularly drawn to Otis from the Alpha Academy legion, who performed in a sparkly singlet and shook his ass in the air to whoops from the crowd. How did he prevent wedgies?

As I watched the wrestlers flip in and out of the ring, I thought: which of these characters would I sleep with if I met them in real life? Even though he was no Luigi Mangione, CM Punk with his difficult, hard-rocker, bad boy persona won out. I would never want to work with him in a group project, but his constant critique of the WWE franchise and his complete faith that his opinions were right made him captivating. He created a complicated and winding narrative for himself, because he always believed he was the main character. CM Punk represents the snob and hater in us all.

When I’d asked my friends if they wanted to go to the WWE Holiday Tour Live with me, all of them said no. They wanted to watch satirical plays about dysfunctional family life and ritzy upper-class schools — Cult of Love, Eureka Day, et cetera. I explained how the greatest cult of love is five sweaty bodies hurling themselves at each other in a ring.

Under the darkness of WWE at MSG, I could be whomever I wanted to be without being embarrassed. I was reminded of Emma, a white woman I knew in college, who loved Asian things — Asian food, Asian languages, Asian men. She told people she was a quarter-Japanese, but once confessed to me that she wasn’t Asian at all. Why did she lie? If she hadn’t, it would have raised eyebrows for her to express so much interest in what she called “the big three: China, Japan, and Korea.” I don’t think lying about your ethnicity is right. But if she had lived life by wrasslin’ rules, she wouldn’t have needed to lie. She wouldn’t have cared.

During intermission, I walked around the hallways, sweating under the fluorescent bulbs and in the heat of the crowd. I spoke with one couple donned in head-to-toe Wrestlemania gear, and asked them how they got into it.

“I watched it growing up,” the man said, looking me up and down. My J. Crew plaid and hipster boots looked out-of-place compared to the graphic tees and costumes most watchers wore.

“Oh, where are you from?” I asked.

He seemed offended. “Long Island. I watched it on the TV growing up. Do you want a picture with the belt?”

I wished I had said that I grew up in New Jersey, also not “the city.” Instead, we took seventeen photos with the belt over my shoulder.

Wrestling relies on earnestness. It’s overacted, over-fought, overdone. Fans have to engage earnestly in the drama. Feuds last for years; people switch alliances; humor is slapstick. Revenge is swift and punishing. But there are always some core themes on display. CM Punk stands for selfhood and rebellion. Iyo Sky reps underdog champions. Ludwig Kaiser performs as a prissy European.

The medical student I was dating was a loving partner who prioritized my needs over his own. When we first started dating, I was ashamed of the ways he deviated from my previous boyfriend. He ate too fast, he had only lived in Michigan and North Carolina, and he hadn’t read Nietzsche. He was so different from the guy I thought I would end up with. (I was a dick.)

But I fell off a steep section of Acatenango Mountain in Guatemala last year and faced injuries that took more than six months to recover. During that time, the medical student became my full-time caregiver, helping me shower, cooking all my meals, waking up in the middle of the night to give me my pain meds. His Midwestern earnestness, which had previously turned me off, became a source of comfort and relief.

While I was recovering, I also began going to Quaker meetings with him for the first time since college. Although I had been devoutly unreligious for years, I found comfort in the silence and community. I needed something, really anything, simple to believe in during this period of intense pain. The “Inner Light,” some ineffable force that moved through us all and took care of us and guided us, provided this reprieve. Everything would be okay.

I asked my friends who didn’t want to come to WWE Holiday Tour Live with me why they weren’t interested.

not my thing…but i would be down to see a play

it’s all fake.

not real. not into it. Sorry

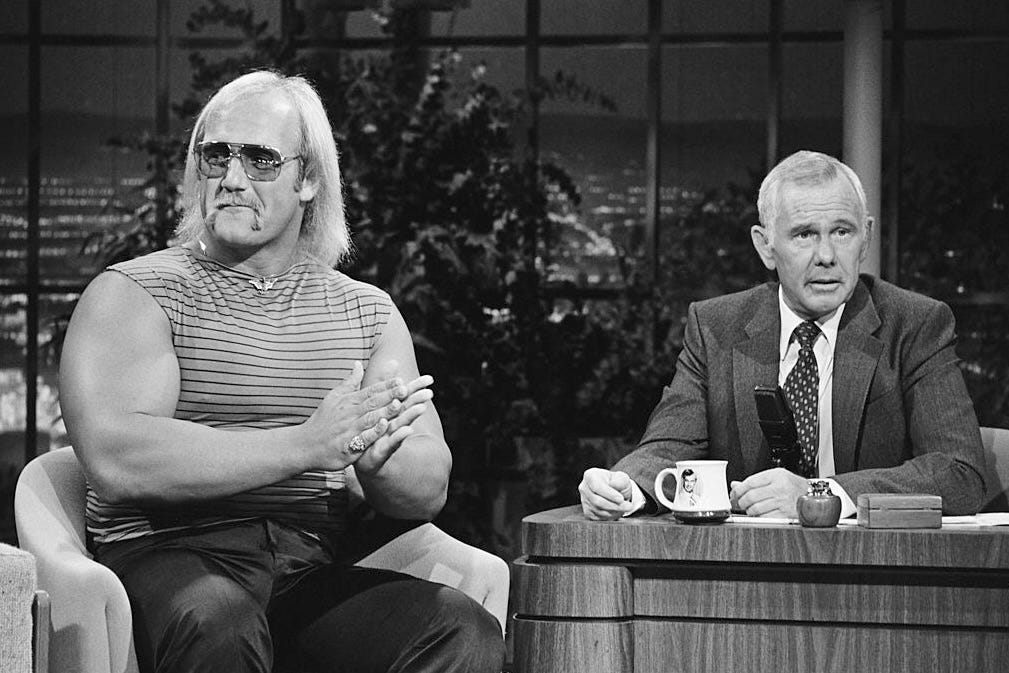

WWE has always been a performance. Many of the theatrical aspects that started in the ‘50s like championship belts and knee-high boots remain part of the franchise today. In the ‘80s, WWE came to the forefront of American media with Hulkamania, Hulk Hogan even gaining enough popularity to host Saturday Night Live. Monthly pay-per-views turned into live broadcasts turned into Netflix specials.

All the fans, except the young ones, told me they knew it wasn’t real. But they liked the story behind the wrestlers. They liked the personal feuds and outspoken judgements. They liked the other fans and the community and the outfits and the culture.

Although WWE lore was undoubtedly complicated (the will-they-won’t-they with Dominik Mysterio and Liv Morgan has kept me on the edge of my seat), the roles were simple. The faces and villains were obvious from how the crowd responded to their entrance, and the way they dressed and acted. Villains were ignoble dicks who got steel chairs and hopped out of the ring when the going got tough. Faces were honorable and kept fighting even though they were cheated. They didn’t give up. During the show, I found myself sinking into the simplicity. Why couldn’t I let myself love simplicity in real life? Why couldn’t I admit to myself that simple didn’t have to be negative? Why did everything have to be complicated in order to be real and thus desirable? What did the realness of something even matter? When times were tough, realness, like authenticity, felt like a load of crock.

At the end of Stephen Florida, Stephen enters his dorm room and it’s unclear who’s standing here. Frogman, the alter-ego haunting him, or Mary Beth, the woman he loves. But I’m not sure if it matters. The novel questions the importance of realness over obsession, logic over feeling. Told in first person, we go through Stephen’s intimate thoughts, “My asshole is the dark zero,” to his inability to process the end of his wrestling career: “Wrestling has kept me busy for about ten years but I’ve been worrying more and more that it’ll do nothing for me once it’s over.” Regardless of who’s in his room, Stephen recognizes that he can’t run from the inner world he’s created in pursuit of wrestling glory, and faces at least a part of his manifestations and fears, and we hope he comes out better on the other side.

People streamed out of MSG after the final match. A boy walking down the stairs in front of me told his father, “This is the best day of my life. I’ll remember this day forever.”

Walking home, I got a text from the medical student, interrupting my daily listening of “Danza Kuduro.” My hands were cold from the winter air. A trash bag spilled open on the sidewalk, its plastic black body limp and undesired.

Miss you meep

I wrote back, I love you so much meep.

Walking with my head down, my boots slapping the dirty ground, I was reminded of one of my first nights in Michigan two years ago. I had just moved there, devastated after my breakup, and was living in an old house alone in Old West Side. Scrolling through Reels on my phone, I stopped when I saw one of a man constructing a large chocolate giraffe. It was ridiculous. The dark body was held up by thick, silver chains hanging from the ceiling. But when he pasted on the wavy tail, I wanted to cry. I dug myself deeper beneath the covers. It wasn’t real, but it was beautiful.

Olivia Cheng is a Zell fellow at the University of Michigan. Her fiction can be found in The Threepenny Review, The Georgia Review, Guernica, and more.

This was great and gave me insight into WWE, a world I knew nothing about. I loved the way you wove in the personal with the wrestling. And the philosophical––what's wrong with simple?

And all of it written in a quietly beautiful way.

Looking forward to more introspective blogs about High Culture at TMR.