A few years ago, the novelist William T. Vollmann was diagnosed with colon cancer. The prognosis wasn’t great but he went ahead with the treatment. A length of intestine drawn out and snipped. It was awful but it worked. The cancer went into remission.

Then his daughter died.

Then he got dropped by his publisher.

Then he got hit by a car.

Then he got a pulmonary embolism.

But things are looking up.

William T. Vollmann spent “twelve or fifteen years” researching and writing a novel about the CIA called A Table for Fortune; as of this writing it has a few back-channel blurbs from editors and assistants who’ve caught glimpses and say it might be his masterpiece, or at the very least a new sort of achievement for him. But when he finished it, in 2022, he turned it over to his publisher, the final installment of a multi-book contract (although even that part gets complicated), and that’s when, to use Vollmann’s words, “Viking fired me.”

His publisher of thirty years.

It’s more complicated than that.

For starters, when he first turned it in, A Table for Fortune was 3,000 pages.

But word count wasn’t the only issue.

Vollmann’s daughter Lisa had a drinking problem. It was worsening for years. Homelessness, hospitalization, dangerous encounters. Vollmann, who’s never owned a cellphone or used the Internet, bought a burner phone so he could call her every day at noon. If she answered he would offer his studio, tell her she should sleep there instead of outside, on the street, or at the shelter where some woman had tried to kill her.

She’d tell him no.

Mostly, she didn’t answer.

Lisa died in 2022. A year later he wrote about the whole situation for Harper’s: about Lisa, Viking, the novel.

He concedes in the essay, regarding A Table for Fortune, that maybe the untamed sprawl and uncharacteristic number of typos were a sign that he wasn’t paying as much attention in the final stages as he normally might. Fine.

He’ll grant them that.

But there was other stuff too — and this’ll sound craven, to be so business-minded about books when really, as Vollmann will be the first to tell you, his work has never sold many copies anyway. His editors and copy editors and publicists are true believers. They love the work and believe in him. The word “genius” comes up a lot in conversation and not with qualifiers; just short declarative sentences, wincing into the first syllable. “Jean-yus.”

Plus they’d been together thirty years, him and Viking, and of course they were there through everything he’d just been through: with the cancer, with Lisa, his whole trek through this novel…

But Viking, in their defense, might lean on the case that, if writing novels is an art, making books is a business, and if Vollmann’s job is the latter then theirs is the former.

So for instance: A Table for Fortune employs a number of different fonts to signify different speakers, memoranda, newsprint.

Well, Viking doesn’t own those fonts. And they’re not free..

Vollmann is serious about turning his novels into beautiful books, almost tangible works of art, and if you fan through any of his recent tomes you’ll see it’s never static. Paragraphs go for pages but if you look at the sentences they’re these long serpentine things and then they’re not. They’re short. Clipped. The prose generally chatty and peppered with exclamation points and the typeface often changes and there’s some ALL CAPS writing and then a photo. A drawing. A chart.

Using the specific fonts that he wants in A Table for Fortune, as opposed to some of Viking’s in-house alternatives, would raise the price of each printed copy by “two cents,” as Vollmann claims in a recent appearance on the TrueAnon podcast.

Likely exaggerating.

He’s still prickly about the whole thing, quick though he is to say, in all seriousness, that he isn’t upset, it's fine, and to chant his new mantra that, the one he mentions on TrueAnon and a couple other podcasts while promoting a book in 2023 that turned into a scandal.

It’s the mantra that, six weeks after that TrueAnon podcast, I’m disoriented to hear through my phone in a friendly, congested, one-minute voicemail:

“Nobody owes me a living.”

I spoke with Vollmann about A Table for Fortune last year, and when I told him I’d be editing the hour-plus recording down to a fifty-ish minute podcast, I asked if there were any parts he considered central, or anything he’d like me to omit.

“Just please don’t make me sound angry,” he said. About Viking, the fonts, the novel. “I’m not angry.”

He explained his remorse for the whole thing and a hope that they might work again some day if he’s still around. He said he can feel things “winding down.” With corporate US publishing, for sure, and maybe his career overall.

But anyway.

“Nobody owes me a living.”

So what’s this book about?

A Table for Fortune is a history of the United States Central Intelligence Agency. Half of it focuses on an intelligence analyst, Dave, and the other half on Matthew, his son.

“When Bill mentioned that he was thinking of a CIA book I was so excited about it,” said Vollmann’s agent, Susan Golomb. “I just thought that he could do such a great job. And I'm glad he did [it].” Golomb has represented Vollmann’s work since The Royal Family, which was published a quarter century ago.

Updates about the novel were sporadic and vague over the decade-plus he worked on it, alongside other projects, but eventually Vollmann started hinting, more pointedly than usual, “that it was going to be very, very long.”

Golomb remembers receiving the manuscript alongside Paul Slovak, his editor at Viking, and the two of them having this bleak conversation over the phone where they just sort of echoed each other. “This is gonna be tough.”

Slovak, who retired from Viking in 2023, was Vollmann’s editor since 1990’s The Ice-Shirt, as much a friend as a colleague at this point—an advocate and a handler. For a while, in the beginning, he was Vollmann’s publicist too.

The way Vollmann tells the story about delivering A Table for Fortune to Viking suggests it wasn’t too different from other books, which tend to be long and complex and to pose new challenges about form and content: some heckling about length, cost, headaches and all the rest. “After seven hundred pages,” Vollmann reflects in the Harper’s piece, “[the novel’s] protagonist remained unborn, and my editor found that tedious; on the phone he got sharp about it.”

He nodded along with their points. Heard them out.

Took the feedback home with him and considered it. One thing they suggested was that he remove a long storyline about the CIA’s activity in Angola during the 1970s where they tried unseating a Marxist-Leninist government that would’ve made a good Soviet asset. They sold weapons, propagandized, and recruited mercenaries in an effort to create civil unrest and install a Western-aligned nationalist party.

It’s a blight on the history of the CIA. Not only for its colonialist jockeying but the fact that it failed. Angola aligned with the Soviets. Still, at the behest of President Gerald Ford, then President Jimmy Carter, the Agency showed data to prove that it was hopeless — same way, Vollmann says, that “president after president” had fed young Americans into the Vietnam War just a few years prior despite conclusive certainty, from the start, that there was nothing to gain.

They didn’t care, he says. All they wanted to do was “bloody the Soviets.”

Which might all be true, was Viking’s point, and it’s certainly very interesting — but what’s it got to do with our characters?

And so Vollmann read the whole book again. In earnest. Looking for places he could take stuff out. Storylines that served no larger purpose.

When he finished up and sent the new draft back to Viking, it was 400 pages longer.

The Soviets duly bloodied, Viking terminated the contract.

When asked about the fate of a 3,400-page novel, unmoored from the protections of a multi-book contract with Viking, Vollmann said, in 2023, that it was looking like A Table for Fortune might be published first in Europe. The Ministry of Culture would try to raise one million euro to have it translated into three languages prior to (if not in lieu of) a U.S. release.

Meanwhile, despite Vollmann’s insistence that his career was “winding down” or “coming to an end,” Golomb was shopping the novel around to other publishers. When Knopf passed, she went smaller.

Grove Atlantic passed. It went for consideration at New Directions. NYRB Books.

Finally, after months of negotiation, A Table for Fortune landed with Arcade Publishing, an imprint at the controversial Skyhorse Publishing (home to “cancelled” authors like Woody Allen, Robert Kennedy Jr., and Alex Jones). Golomb had been reluctant to speak about the deal, since Vollmann hadn’t signed the contract, but after waiting a while she went ahead and took my call.

She couldn’t say why he hadn’t signed, “We’ve gone over it a million times,” but didn’t sound worried. His research assistant, a novelist and doctoral candidate named Jordan Rothacker, said he didn’t know much about the deal with Arcade, in terms of the contract’s finer points (i.e., how they were reacting to the font issue, the length) except that Vollmann was “99 percent” happy with it.

When asking if there was a reason he hadn’t yet signed, the questioner is invited to take their pick.

The cancer effects don’t just vanish, plus the treatment created its own trouble, and when prompted to speculate at the state of his grief, the scope of it, most interview subjects just make a small open-mouthed croaking noise and echo the facts: “Guy lost his daughter.” More recently he discovered a blood clot in his lung. The car that hit him in 2023 wasn’t going slowly, either. Vollmann “went through the windshield,” according to a friend; “[it] broke my back,” as Vollmann himself told TrueAnon, and so began his “Percocet Glory Days.” Scooting around his art studio and home with the help of a back brace, a walker, “blibbering and blabbering” with friends whom he realized, for the first time, actually loved and cared about him.

His cancer, last I’d heard, was in remission, and he was done with the walker, traveling to Ukraine to report on life under Russian invasion, feeling good. I asked Rothacker if there were other ailments or projects on Vollmann’s plate that might be distracting him.

Rothacker — for whom Vollmann isn’t just a friend and employer but partial subject of his dissertation — concedes with a breath that the author’s bigger-picture wellness isn’t the sort of thing he’d expect to hear about, at this point.

Vollmann’s health (like his incongruously suburban life in Sacramento) is just about the only thing he’s private about.

Rothacker didn’t learn about Lisa’s death until weeks later; and in that sense he was one of several people in Vollmann’s social-professional orbit who, despite seeing him regularly, would learn more about his loss from his Harper’s essay than they’d ever hear from Vollmann personally.

In the essay, he allots a couple hundred words to it.

A few weeks into researching this article I’d sent enough emails and left enough voicemails with Arcade’s editors that I got a friendly follow-up from their publicist, saying decisively that there was nothing to report at the moment, but stay tuned, and in the meantime please direct all questions here, to the publicity desk (i.e., stop bothering the editors) — an email I was too embarrassed to even answer, working myself into a pretzeled torment about how to report a story The Right Way, and go through Proper Channels of contact…

Then on the first Monday in March, around 4:15 p.m., I got an anonymous message on Reddit. The username was anonymous. The account was years old but the user had never left a comment, never posted anything. A seasoned lurker.

They asked if I was doing a Vollmann story.

I said yes.

They said they worked for Arcade Publishing.

I said OK.

I was at a bar at 6:06 p.m. when they sent another message saying they just wanted to make sure I wasn’t about to submit an article about A Table for Fortune, saying “TFF will never be published in the USA the day before we announce it.”

The weight of what they were saying didn’t really hit me and I wrote back, “No worries.”

They wrote back, “Sounds good.”

And that was that.

Twenty-four circumspect hours later, trying to figure a way to revive the conversation, I got another message from the same person (presumably), this time on Substack, through Arcade’s official account.

“Do you have a number [I can] call?”

I gave it to them.

The next morning at 10:26 a.m. I got an email from Arcade’s publicist, the one who’d asked me between the lines to please quit accosting her editors, whose name in my mailbox ignited such a gut-plunging shame I put my phone down in the cupholder and collected myself before looking again:

Arcade Publishing is proud to announce the upcoming publication of

A Table for Fortune,

William T. Vollmann’s 3,000+ page, four-volume masterpiece

Chronicling the last half-century of American war, life, and politics.

A third anonymous message came shortly thereafter. A text this time. Asking if I was available to talk.

A few things they can confirm so far, without a final edit or mockups:

A Table for Fortune is coming out Spring 2026.

The novel’s text is unabridged.

Arcade has met the author’s expectations when it comes to fonts.

Vollmann originally submitted the novel with suggested breaking points, where the book could be broken into two or, worst case scenario, three volumes. Arcade pressed for four volumes. Vollmann agreed. He’s still tinkering to see where that third break might come in.

All four volumes will be released at once, as tall hardcovers with jackets and endpapers.

They’ll be sold individually, and boxed together in a set.

Vollmann has clear ideas for (and will be playing a role in) the design of each volume, as well as the boxed set, which will — if all goes to plan — sport a photo of George W. Bush on one side, Dick Cheney on the other.

Isaac Morris, the young editor handling A Table for Fortune, felt some light nerves about the scope of the project: the months of secrecy, the slow back-and-forth with the author (to whom everything is conveyed by mail or phone), the grinding negotiations.

Then, even with the contract hashed out and revised (and revised), Vollmann waited to sign.

And now, suddenly, it’s happening.

Morris, 25, comes to the task as a longtime Vollmann fan; his favorite is the debut, You Bright and Risen Angels (1987), specifically the copy on display in his alma mater’s library—the same junior arts college Vollmann attended in the 1980s, Deep Springs, known for its curriculum that explores academics all morning, followed by farm labor through the afternoon. The school’s copy of the book was inscribed by Vollmann with a note that said, as Morris recounts (“if I’m remembering correctly,”)

“Mr. White [a character in the novel] is not L.L. Nunn [Deep Springs’s founder],

And School of Matthew [the book’s setting] is not Deep Springs.”

When negotiations began, said Morris, it was hard to tell which concerns were Golomb’s and which were Vollmann’s, harder still to determine whether the answers/solutions/suggestions he supplied were ticking the dial in Arcade’s favor. Talks could sometimes stall for weeks at a time as author and agent spoke with other imprints. Now that everything is settled, he wonders if it was really so up-in-the-air as it felt. “A lot of the conversations,” he’s come to believe, “were [about] getting to know each other, building trust.”

Another discovery about A Table for Fortune, looking back: the word count wasn’t actually so intimidating to other publishers. Interest in A Table for Fortune was wide and earnest when Susan first took it out on the market. The reason it ended up where it did, says Morris, is that “Arcade has Tony Lyons,” president and publisher of Skyhorse.

Morris tells the story of going into Lyons’s office to make a pitch about acquiring A Table for Fortune. He found the whole project compelling, and he was a little mystified about other publishers’ hand wringing; in an added precaution against whatever folly might come from being somewhat new in publishing (his “known unknown”), he sat down with Lyons and sketched the situation in starkest terms: the word count, the fonts, the expenses and legal hurdles.

Lyons said, “Absolutely. Let’s do it.”

In 2023, after acquiring Regnery Publishing (a conservative imprint), Tony Lyons was profiled in the New York Times as one of the largest small publishers in America (i.e., non-Big Five).

Skyhorse has 10,000 titles and twenty-six imprints, according to its website, but the publisher is best known as a kind of catcher in Cancel Culture’s rye, salvaging controversial books that — in the most opportune cases — were already picked up by a Big Five publisher, paid for, and then dropped, at a loss, because the authors were controversial. There was Woody Allen’s autobiography, Apropos of Nothing, which was canceled when employees at its original publisher, Hachette, staged a walkout; he grabbed Blake Bailey’s biography of Philip Roth after W.W. Norton canceled the book’s run, within a month of release, following accusations of sexual assault. Perhaps their biggest seller to date is Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s The Real Anthony Fauci: over a million copies.

Lyons, dogmatically committed to free speech, has been described as “a libertarian” or “old-fashioned liberal,” but his platforming of far-right icons, like conspiracy theorist Alex Jones (“the most persecuted man on Earth,” according to his latest book jacket), inclined the Times toward depicting him as less a leader in the New York publishing scene than a bookselling figure in the realm of right-wing media, citing his co-chairmanship of a super PAC that supported Kennedy’s presidential campaign in 2023.

Lyons has found, in Vollmann, both a literary heavyweight (someone revered in those publishing circles) and another model for his cause (platforming an artist whose expression was reined in, albeit for different reasons). Vollmann isn’t a right-wing figure, by any means, but his experience with A Table for Fortune fits a popular impression about modern publishing, one that aligns with broader criticism of the political left: that it champions politics over free expression, that its campaign to amplify marginal voices doubles as a campaign to silence popular positions. The critique was solidified by choices like withdrawing Dr. Seuss books from print, for fear of racist messaging, or by editing Roald Dahl’s books for children so that they’re better-aligned with modern progressive attitudes (the young protagonist of Matilda, as Dahl created her, was an avid reader of Joseph Conrad and Rudyard Kipling; editors at Penguin Random House changed that to Jane Austen and John Steinbeck).

Neither Lyons nor Arcade will be doing anything to press their own thumbprint on the final product with A Table for Fortune. What Morris maps out in our phone calls is a book that will be distinct for its loyalty to the author’s vision.

There’s almost a paradox about it, like Arcade’s commitment to an immersive reading experience becomes (due to the facts surrounding its release) an argument for something outside of that experience. A book about one thing is drawn, by its industry and times, into an argument about something else.

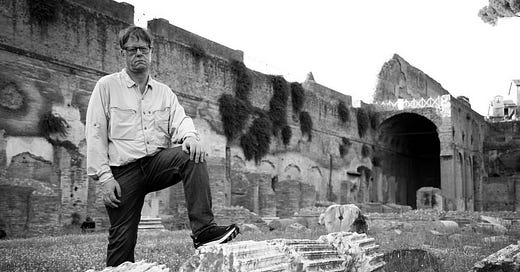

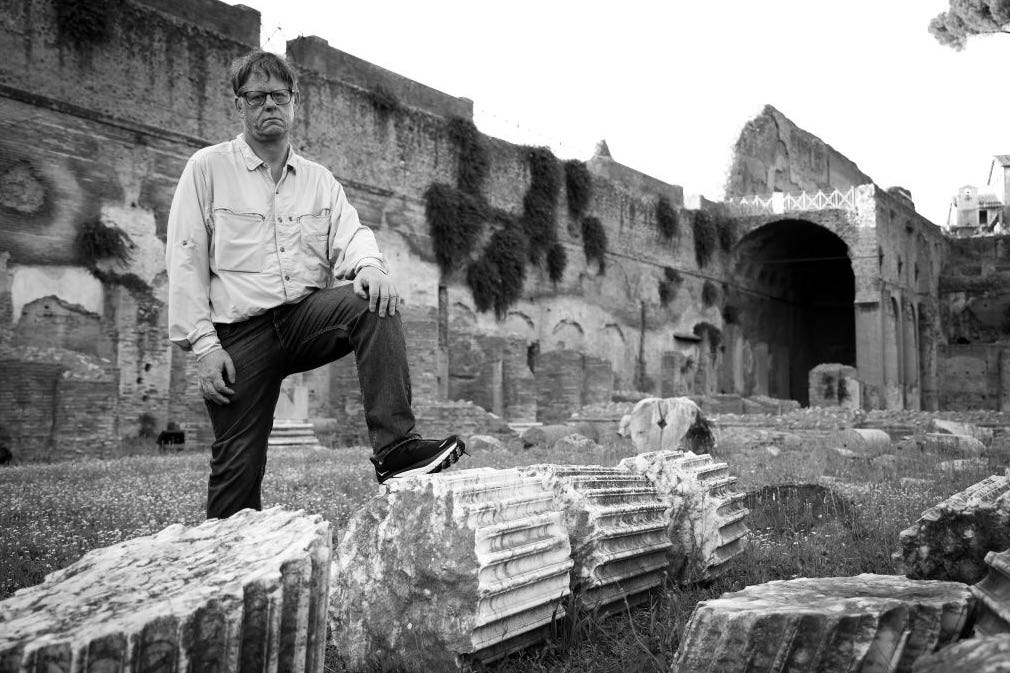

I was able to speak with Vollmann after someone gave me the phone number to a bunker-like structure that used to be a Mexican restaurant before he bought it in the early 2000s and, with the help of his dad (a tool-savvy professor), converted the space into an art studio/apartment. There’s a closet, a kitchen, and space to sleep. Paintings on the walls. Vast tables for works-in-progress (photos, prints, drawings, manuscripts).

Homelessness in the area is high and over the years Vollmann’s had to take greater measures against break-ins and damage. There are bars on the windows and Vollmann chuckles through an anecdote about how he was sitting here working on something in the studio one night when he looked up and there’s a hand arching in through the grating. He tells the story for laughs but look around. Those windows are covered by bookcases.

His parking lot remains host and haven to sleepers. Sometimes when he’s not around the cops will come and roust people, confiscating or destroying their tents, their carts, which in many cases carry their medicine. Sometimes he’ll write a permission slip saying he’s the owner and that So-and-So can stay here. Sometimes the cop’ll honor that.

He used to spend a lot of time hosing waste off the pavement but now it’s better for everybody if he just delegates those tasks. He’ll ask one of the visitors (campers? lodgers?) if they’d like a few bucks to sweep up and they’ll usually say yes and do an OK job. Friends tell him, Sweet gig, Bill: invite them to make a mess, then pay them to clean it up. Bill says, Oh sure.

He says it fast, like one word: Ozure.

People say Vollmann’s got guns all over the place but nobody’s written about seeing one. Not here at the studio anyway. Back in 2004 a French journalist went to Vollmann’s actual house and they were drinking whisky and getting along so great that when the topic veered toward guns, of which the French are notoriously bereft, the journalist wanted to have a look at his arsenal and Vollmann said, Oh sure, but not today because they’d been drinking and you have to be sober around guns. So the French guy came back a couple days later. Said hello to Vollmann’s wife Janice who was friendly but uneasy. Lisa was five at the time. Darting around those white-and-beige sofas. Vollman went and brought all these guns out from behind the garage and laid them on a table — a submachine gun, a Sig Sauer — and the two of them ogled it and Vollmann held court until his wife wasn’t liking this anymore and so they put the guns away and went ahead to the studio where it’s cozy and homey anyhow. The wall art is graphic: photos of sex workers, painted vulvas and mouths, outsized drawings of Vollmann’s own marbled female alter-ego Dolores. Even the doors are covered.

Visitors (i.e., the ones he brings inside) are propositioned as soon as they step through the door: whisky or tea? Recordings make it sound like you can’t empty a glass before he’s halfway off his chair, tilting at you, “Another shot?”

It’s a needed retreat since, frankly, even after all these years he’s never come to feel quite at home in Sacramento. He’ll praise its better qualities: “People are very friendly. It’s a very quiet, dull place, which means it’s a good place to raise a child.” He just never felt at home here.

Vollmann’s prints and paintings sell for mid-three and low-four figures, through auctions and a dealer who recently died, but it’s not unprecedented for somebody to visit him at the studio and after sitting around chatting and drinking he just hands them one.

That bookcase where a window should be — see how it’s all titles about George W. Bush, Cheney, foreign policy, Iraq: that’s A Table for Fortune stuff. The novel isn’t part of his Seven Dreams series (of which five heavy volumes are currently written), but abides by their same standard of historical realism. Vollmann’s method is this: he reads a library of research about his subject and setting, fills notebooks with facts, and then goes to the location, believing that, even if he’s removed from his subject by a couple centuries, you can always find a deep connection with your material by going and sitting in a field (or on a tundra) and looking around and saying, of your historical characters, “This is what they saw every day.”

He’s not terribly staunch about it but, the way he describes his approach, it’s like the freedom to create is something to be earned. “It’s too easy to go on making things up.”

Vollmann’s favorite part in the novel-writing process is when he’s roughly three-quarters done. That’s when he knows his subject, his characters, the place and time and rules, and he can just “walk around” in the story, so to speak. Facts and imagination become one.

With A Table for Fortune — which focuses heavily on the administration of President George W. Bush — you can ask him just about anything about America’s recent wars (about modern warfare itself) and he’s ready to chat. Like Osama bin Laden’s assassination and alleged burial at sea, for which there’s an Official Narrative claiming that, after Navy SEALs raided his Abbottabad compound in Pakistan, they took his body out over the ocean on their way home and gave him a proper Muslim burial.

Well, Vollmann’s read the Official and Unofficial Narratives and he’s decided that the version best-aligned with reality, such as he’s come to know it, is the one reported by Seymour Hersh: i.e., that the Pakistani government knew where bin Laden was hiding all along. They were holding on to him as a sort of bargaining chip (imagine the leverage: the ability to gift an incumbent U.S. president, six months before his election, the hiding place of the most notorious mass-murderer in American history, old and feeble, practically unprotected) and that the “burial at sea” never happened (unless you’re very liberal with the word “burial”).

After all, there was no Imam on the mission. So who would lead the Muslim prayer? SEAL Team Six?

No, in Vollmann’s version (as in Hersh’s), the administration colluded with Pakistan, SEALs flew in, they shot this old man, took his body onto the helicopter and then started clipping off parts of him and throwing them out over the water. Into the dark.

After all, says Vollmann, “Why not?”

He believes in a half-flippant way that there’s a Navy SEAL somewhere in this country with pickled finger in a jar.

Vollmann might stay here in the studio for one or two weeks at a time to write that sort of thing, but he lives someplace else with his wife (a radiologist), a two-story home whose neat-and-airy atmosphere can give people pause. Vollmann’s got an eye problem called strabismus: they’re not perfectly aligned and he can only see through one at a time. “When I was a boy it would make me self-conscious. Balls would hit me on the nose.” His depth-perception isn’t great. He says it’s the minor handicap that first drew him toward other handicapped people — then, after a beat: “like pimps, whores, and murderers.” So maybe that’s a joke. The eyeball thing makes it so he can’t drive.

When his wife was still in medical school they lived for three years in a one-bedroom apartment above Sloan-Kettering in Manhattan, then headed west for her job. A young D.T. Max, visiting their Sacramento home in 1992, made note of the open space, the neatness, the creamy furniture. On a coffee table — “one discordant note” — the latest issue of Special Weapons.

Vollmann himself described the place as “petit-bourgeois” and here, on a Sunday morning over the phone in 2024, you can hear one or two dogs barking over his shoulder as you introduce yourself, and ask if now’s a good time to chat.

Readers of his work are probably more at home in the studio with its prison windows, its razor wire tiara; the walk-in cooler now a wardrobe for Vollmann’s clothes and the many dresses of Dolores. There’s a landline in a closet that he doesn’t really answer. Instead of an outgoing message, like “Please leave your name and number…,” Vollmann has recorded what sounds like a stick whacking an aluminum can three times, followed by the beep. State your business in twenty seconds or less.

If he’s interested, he’ll call back a few days later; the screen on your phone will spell JOHN Q. PUBLIC, all caps, and when you answer he’ll say, “Hi,” real chipper, “this is Bill Vollmann.”

I hear it a few times as we phonetag toward an interview.

Finally on a Saturday night we catch each other and he says he’d like to give me his home number for tomorrow’s interview.

Then with gravity he adds, “Now promise me first that you will nevvver share this number with anyone.” The delivery’s a little tongue-in-cheek, the way Wonka would say it knowing you’ve been approached already by Slugworth, but he’s serious. Vollmann’s work has garnered threats over the years and even though the FBI has finally and categorically decided he is not the Unabomber, after investigating him for several years, he’ll still occasionally go for his mail and find the envelopes aren’t sealed but re-sealed. In an unbroken package of books, he’ll find the spines all slashed and searched.

He’s gone lengths to isolate his work and home life so that his family won’t feel any hassle.

He leaves that stuff at the studio.

I delete the number after our talk.

A Table for Fortune was meant to be the final installment of a three-book deal with Viking, which would have unfolded like this:

Book One is Carbon Ideologies (2018), a nonfiction work about climate change.

Book Two is The Lucky Star (2020), a contemporary novel set in Sacramento’s tenderloin neighborhood.

Book Three is A Table for Fortune, an epic-length novel about the CIA.

But the contract started unraveling from the beginning; the first book, Carbon Ideologies, was nearly 2,000 pages in manuscript form.

Imagining Susan Golomb receiving Vollmann’s manuscripts brings to mind a boxy bundle of butcher paper and twine thudding her doorstep twice a year, but Golomb says the receipt of Vollmann’s manuscripts is trickier than that, something she delegates to her assistants at this point, who’ve been savvier at navigating Vollmann’s progression from floppy disks to CDs to the USB flash drives that carry his manuscripts through the mail. “They’re too long to transmit electronically.” (Not that Vollmann could email it, having never used the internet, but an eleventh-hour crisis will sometimes occasion an email from his wife’s account.)

The trickiness, in other words, is that Golomb never knows how long it is until the document turns up on her screen and she starts to scroll down.

And down.

Imagine you’re commissioned by Viking to help with an editing problem. Someone slides you a binder and says, “We need this to be thirty percent shorter,” and so you start fanning through it, you haven’t read the thing, but you notice there's a fair amount of white space: extracts from newspapers, manuals, signage. Islands of text with white all around. So that can be tightened, surely. Maybe cut! Plus the photographs (often depicting things he’s described in reams of seductively chatty prose). And if you’re taking out the photos you’ll certainly be cutting back on the tables: these gray-backed rectangles that unfold for pages at a time, not just arresting the eye but widening it, crawling as they are with numbers, formulas, strange scientific metrics by which, having already explained his computations, Vollmann wants to make sure the reader can turn to these resources and vet the math for themselves.

“Move this, clip that, scrunch these” — you can see how such a book might be squished into something more commercially-friendly, the sort of “practical” cost-saving concessions to which an author might be induced when reminded that, for them as well as the publisher, a dollar saved is a dollar earned.

But Vollmann said no. Same as he did back in 2000, with The Royal Family, the first deal he made through Golomb, for which he took an alleged 30% pay cut in exchange for leaving the manuscript at its proper thousand-page length.

Amiable but firm, he told Viking that he was ready to quit over this. Take the book elsewhere.

Viking gave in. Carbon Ideologies was released in two volumes, roughly 600 pages each, between April and June of 2018. Fans glommed onto it right away, critics praised its artistry, scientific acumen, and persuasively terrifying verdict about the environment (with variously-worded caveats about what the New York Times called its “undisciplined” size).

Editor Paul Slovak, talking about the book seven years later, maintains that “if Bill had been willing to cut a certain number of pages…we could have done [Carbon Ideologies] in one volume, and it would have been a much more impressive presentation.”

Apart from the inherent difficulties of marketing a two-volume book (getting readers interested in the same terrifying topic twice, in one year, $40 each time), Carbon Ideologies was a unique case in that, by breaking it in half, some of the material from Book One had to be repeated in Book Two. A wasteful offense, on its own, and doubly questionable in a book about the apocalyptic consequences of waste.

Quick and comprehensive as he is, years later, to recount the differences and obstacles of a certain project, Slovak never sounds bothered in our conversation. It aligns with his reputation. He’s “gentle but remorseless,” in the words of T.C. Boyle, another of Slovak’s decades-long clients. Never an edict, only ever a suggestion, maybe a request.

Boyle’s relationship with Slovak operated on similar terms as Vollmann’s: he never wanted feedback unless he requested it and, when he requested it, what he wanted from Slovak was a “soundboard,” not a prescription. And Slovak’s good at that: reads the book, shapes his opinions, and then what he does is he stacks them up inside himself (he’s very tall) and only when it seems appropriate, vital, or requested does he tilt his head back and dispense, Pez-like, the one judicious insight.

“It’s what every author wants,” said Boyle. “I would tell him, ‘OK, Paul, here’s the new book. I want you to call me up when you’re done with it, I want you to just give me praise. Then wait a day or two. Then call me back with any reservations you might have.’” The word egoless comes up. “Which is ideal,” he continues, “because my ego is huge and these books that I’ve written are things I’ve worked on, every word, for sometimes years.”

His tongue’s in his cheek about the huge ego, but only sort of; after so many years together, and so much success, the confidence grows. As does the faith. And the comfort.

Seems natural that there might be some bafflement, some indignation, when after so many decades and so many books the author submits their latest and sees a slew of suggested changes.

Like the betrayal wouldn’t be the judgement inherent to edits (anybody generous to give thoughtful edits to your writing is probably not the judging sort), but an implicit suggestion that, after so many years, they expected something different from you.

Vollmann, on the other hand, always wanted feedback.

And Slovak delivered.

Still, he acknowledges, Vollmann could be “very stubborn about cutting things. Very stubborn.”

Another way of looking at why things fell apart between Vollmann and Viking is that it was less about A Table for Fortune than relationships. Four years after Viking makes a huge concession on Carbon Ideologies, breaking what was supposed to be one difficult expensive book into two difficult expensive books, here comes Vollmann with a novel that — by the same laws of bookbinding and selling— would have to be split into three volumes, if not four.

First he breaks a three-book deal into a four-book deal; now he wants seven?

Even if he’s not asking for more money to do it, the expense goes way up; and what about promoting it? You think the Times is gonna review every volume?

This is the view that says Vollmann is unreasonable.

However.

What muddies the view that Vollmann’s being unreasonable, and that the show simply could not go on, is that folks have been saying he’s unreasonable, on these exact terms, for thirty years, and getting along just fine.

Dan Halpern heard it all the time and occasionally said it himself. He’s an Executive Editor at Knopf right now: big shot with hair to match, a tall white curly plume, a 5 o’clock shadow from breakfast onward. He’s a poet. A foodie. Avuncular. Friendly voice. In a previous life, as founder and publisher of Ecco Press, Halpern worked with Vollmann on four books of nonfiction. I asked him how they approached editing, since each of those books is a tangle of Vollmann’s first-hand reporting, plus characteristically vast research; I’m wondering if it had to be more hands-on than the fiction, if they sat with red pens at a table with piles of manuscript…

“We never sat at a table except to eat or drink.”

They first got acquainted when Halpern saw that McSweeney’s had published, in seven volumes, Vollmann’s unabridged Rising Up and Rising Down; he called Golomb and asked if there was any way to do a digest of those volumes in one book? 300, 400 pages?

In the end they got it down to 700, paperback: tall black elegant thing with a good amount of images left intact.

Part of the obstacle for Halpern, editing Vollmann’s nonfiction, wasn’t just the size of the manuscript, or the quality of the work, but a personal appreciation for the author’s work ethic. “He’s done things nobody else would do. I remember once he tried to get me to go out with him to ride the trains with the hobos. So I said, ‘It’s a felony if you get caught,’ not to mention the physical part of it.”

When it came to the editing, Halpern encountered a brilliant and companionable author who happens to “write long,” in Slovak’s words, and isn’t keen to pare it down. A different challenge was the subject matter: it was obscure (like Kissing the Mask, his book about Japanese Noh theater), too grim (Poor People, in which Vollmann travels the world interviewing impoverished people about what they believe to be the cause of their hardship), or too niche (Riding Toward Everywhere, a self-professedly aimless account of his experiences in train-hopping).

So if the challenges are all basically the same, in the 2020s, as they were since at least 2000, then why are they no longer negotiable? What’s changed?

According to both sides: publishing.

It’s the only point on which Slovak sounds especially weary. “It’s harder now because of the extra production costs going up, everything’s more expensive…” He trails off, like we’ve all heard this explanation before, like it’s not only tedious to reiterate but kind of misleading.

Slovak was Vice President and Executive Editor at Viking Books, one of the higher-ups in 2023 who took the Penguin Random House buyout, which targeted employees aged 60 and over who’d served for fifteen years or more, and was ultimately, he says, “kind of un-turn-downable.” No hard feelings. The time was right and the terms were fair. Plus, he’s still involved, having written a history of the publishing house for its hundredth anniversary. It’s in copyediting as we speak.

No resentment in his voice, but something personal:

I mean what happened after the pandemic was that there was no more face-to-face interaction in the business. Some of that has come back, but at Penguin Random House [they basically] said, “If you want to spend the rest of your career working at home, you can do that.” And so then what happened was that all meetings, every single meeting, was virtual. I got so tired of that.

In earlier days, when a conference was called, you’d see twenty people in the office; now, post-Covid, it’s “maybe more like five people.”

This comes up a lot among those who’ve been in the industry a quarter century or more, but seldom in such plain language; there’s some coded griping about readers being too sensitive or censorious, complaints about a lower-than-ever tolerance for risk and a higher-than-ever deference for the bottom line — but underneath the more business-minded or socially-aggrieved arguments seems to be a feeling that publishing has just gotten chillier. Facile. Virtual.

T.C. Boyle confirms the impression when I ask about his later visits to Viking, where he was once a regular in Slovak’s office with its countless posters and photos, colleagues coming and going, chance encounters; he laments, now, how business has “moved into these inhuman spaces. [It’s] all very regrettable. I choose to remember the glory days, when it was very human,” and one’s experience of the workplace was chatty, social, “busy. Very busy.”

Soumeya Bendimerad Roberts is a literary agent at HG Literary and Vice President for the Association of American Literary Agents (AALA) — she also started her client list working for Susan Golomb, as Foreign Rights Director, where she occasionally “slapped some wrists” on Vollmann’s behalf, sending a notice of penalty to some foreign publisher who violated one of their contract’s many no-goes, like spelling his name wrong. (“Two Ls. Two Ns.”) Roberts worked with Vollmann and Golomb in the early-mid 2010s, and saw a lot of publishing’s recent cultural/corporate/technological changes taking shape.

So she’s had this conversation a lot, with newer and older generations alike, and she’s specially suited to see both sides, having been there for the latter part of How Things Were (the boss at her first publishing job still smoked in his office). Roberts joined Golomb’s agency as Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers (2013) was gearing up for release and everyone still had confetti in their hair from Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom (2010 — an author of two consecutive Oprah Book Club picks; a novelist on the cover of Time Magazine).

“I hear those concerns,” she says about those who grieve the once-lush world of New York publishing, “but one thing we often talk about,” as a counterpoint, “is the accessibility of New York.”

More specifically, the lack thereof; it’s publishing’s enduring irony that a career of constant work and modest pay happens to be concentrated in one of the most expensive cities on Earth. Roberts herself worked seven days a week when she moved to New York for a job in publishing — and that was with several years’ experience on the West Coast.

“Having a New York-centric industry is problematic for an equal opportunity-type of world.” Going virtual to a degree is a way of “opening the door to a lot of talent that wouldn’t have had the opportunity before,” she said.

“Virtual work is exhausting.”

Uniquely and acutely. It’s hard to explain why five hours of Zoom meetings is so much more tongue-dryingly miserable than hopping across actual conference rooms, but it might have to do with the fact that remote availability, wherein our jobs exist on laptops and smartphones, creeps ever-closer to constant availability. “That deep [isolated] work of editing and reading is so much harder to come by,” she said, and there’s definitely something dispiriting “about not being in a room together [with colleagues], talking face-to-face in a way that’s generative. There are so many more meetings and emails — sometimes you just need a good chunk of time to read, or have a conversation, or write an editorial letter. [And that’s] become extremely challenging to find.”

One high-profile Vollmann fan (“I read everything that motherfucker writes,” he told me last year, in a Zoom interview about Michael Silverblatt) is the novelist Junot Díaz, who for the past couple years has published regular essays on literary craft and reading through his Substack newsletter StoryWorlds. Following up in an email, Díaz explains that “a writer of Vollmann's astonishingly proteanic talents is always going to have trouble in the book business. Especially in the current iteration of the book business which with every passing year is more business and less books.”

Slovak, somewhat allowing of Vollmann’s argument that his novels don’t earn any money, points out that The Dying Grass (2015), Vollmann’s thousand-page historical novel about the Nez Perce War, received some of the best reviews of his career and, despite being released in a then-astonishing $55 hardcover, sold about 5,000 copies (no word on the what the paperback sold, whose covers are almost polka dotted with blurbs along the lines of, “The reading experience of a lifetime”). But 5,000 isn’t too bad, he suggests. Especially when the critical reception is so unanimous and glowing.

Alas, blurbs aren’t dollars, and nothing’s guaranteed.

“That sucks for Vollmann,” said Díaz, “and for anyone who cares about literature.”

If Golomb sounds remarkably at-ease, talking about the situation with A Table for Fortune, it’s worth noting she’s seen Vollmann in big messes before.

They met in the mid 1990s, when Vollmann was living in New York. His girlfriend (now wife) was in medical school. He was hanging around with Jonathan Franzen.

Franzen was friendly and withdrawn, a trendy intellectual — reading Semiotext(e), then a publishing house that also put out a magazine — with a not-so-trendy lifestyle. He was young and described his married life as hermetic. He didn’t even seem that comfortable in New York. In the early 1980s he went to a Cuban restaurant and ate some bean soup with glass in it; for the next couple hours, waiting to see an emergency room doctor, he stared at the woman on a gurney right across from him, leaking “pinkish fluid” from what looked very much like a .22-caliber hole in her stomach.

When he met with Vollmann in the early 1990s he had two novels to his credit and a marriage that Vollmann casually told him didn’t look so great. His career was feeling stagnant in a way that seems meaningful in retrospect if you know that there were two consecutive blockbusters ahead of him, at roughly ten-year intervals, following his second novel in 1992; but at the time it was just frustrating, depressing. His essays from the 1990s, collected in How to Be Alone, capture it well. Even when Reporter-at-Largeing he writes about Post Office employees and federal prisoners, whose uniforms are indeed very different; the latter essay includes a manifesto about the state of American reading that’s brilliant and incisive but vaguely anguished throughout.

A stark contrast to the struggles in his own creative life was Bill Vollmann, his “only male writer friend,” who “led the least hermetic life imaginable, traveling the world, watching people die, narrowly escaping death himself, and consorting with prostitutes of every nationality. He kept proposing, in his flat-voiced way, that I do journalism or take a trip to some dangerous place. There, too, I tried to follow his example.”

Vollmann at this point had a reputation among some of the cooler literati as a kind of Gen-X Pynchon, a Gonzo author who risked his life for his work: sequestering himself in the “Arctic wilderness” to research The Ice-Shirt, or getting held down and burned with cigarettes by young men (an episode he applied to Fathers and Crows). These were huge ambitious novels that were probably more appreciated than read. But Vollmann knew who he was and what he was doing.

For cash, at the time, he was getting a toehold as a journalist, most successfully at SPIN magazine, where founder Bob Guccione, Jr. remembers him as “the greatest writer SPIN has ever published.”

Also, one of the most verbose.

Guccione would give modest-length assignments, Vollmannn would go off to the scene, and two weeks later send back a heavy brown envelope with 30,000 words. “And handwritten,” Guccione adds. “We’d have to type it up. Once it was 80,000 words, and I said to him: ‘I’m not even going to read this.’”

Says Guccione: “His were the only expense reports I ever saw that listed prostitutes as a legitimate expense.”

But the journalism was always in service of two things: paying bills and researching a book—of which there were always three or four in rotation.

“After we made a pact to trade our future manuscripts,” writes Franzen in his essay about their friendship, “I got a thick mailer every nine months, while my own next book was so long in coming that I forgot I was supposed to mail it to him.”

Part of what kept Franzen afloat was his agent, Golomb.

Golomb represented Franzen even before going into business for herself. She worked as an assistant at the previous agency, where they met, and in selling his first novel, The Twenty-Seventh City, Golomb would later be able to claim the honor of spotting, grabbing, and championing one of the generation's greatest talents; “and [she] was rewarded for that,” Franzen said in an email, “by being fired by her boss.”

“When [Susan] set up on her own, around the time [my second novel] Strong Motion was ready to sell, it was a no-brainer for me to sign up as her first client.”

Golomb was living, at the time, what she describes as her “East Village-y, lower-east side” period: the vibe is a streetlamp-colored, martini-clinking, book party life; shouty lean-in conversations at bars, live music, countertops that pulse. She says it to strike a contrast against the jump-cut to now, where she and Paul Slovak have homes not far from each other, a bit north of the city, and still meet up to go hiking. Where Paul’s retired early and doesn’t do as many book parties but he sits on several boards and stays engaged with the business. Reads a lot. Recently, at a bar, he told one of his friends (whom he describes as a very successful novelist) that he’d like to read the guy’s new book, in manuscript. The friend is grateful, and offers to pay him, and Paul with a laugh says no.

Ask her when she and Slovak met professionally, versus when they became friends and started going to live music in groups, the partition’s a bit fuzzy. Through the fog she remembers a book party for Richard Hell. Patti Smith was there.

That’s the mid-1990s. Around this time Vollmann was working on a long essay that would eventually become Rising Up and Rising Down, a 3,352-page meditation on violence, which Golomb would later, miraculously, manage to sell twice: first as a sort of unabridged prestige set with McSweeney’s (seven hardcover volumes in a crimson slipcase, $120), and then one more time, in abridgement, to Dan Halpern.

McSweeney’s Internet Tendency published a brief oral history of the book’s production: mostly a Kafkaesque portrait of fact-checkers, in obscure corners of grad school libraries, tracking down and verifying the four or six quotes on a single page. Golomb talks in that piece about Vollmann wanting to sign with her on the condition that she sell what he referred to as “my ball and chain,” this 4,000-page Grendelscript with photos, endnotes…

If Vollmann sounds reticent or arrogant, issuing an ultimatum like that, it’s worth noting that they were already acquainted at this point. He wasn’t rapping a cane on her office door, sauntering in with a proposal.

But he might indeed have been a little edgy about the deal. Having negotiated so many of his own book sales, Vollmann was skeptical about the utility of a literary agent. Privately he questioned Franzen about the commission he paid to Golomb for his work. Was it really worth it, when you could be doing it yourself? Franzen assured him that, apart from being smart and tenacious (the myriad qualities echoed by everyone in her professional orbit), agenting was her full-time job and, yes, she was worth her fee.

Maybe Vollmann was convinced, maybe not. Even after they paired up, and Golomb sold his 1,000-page The Royal Family as the first of a two-book deal, Vollmann would spontaneously ask writers, even years later, if they had an agent or not, and why, and how they felt about it.

But making those book deals takes time, and time spent selling books is time taken from writing them.

So he asked to meet Golomb and, during a party at Paul Slovak’s apartment in 1996, Jonathan Franzen stood by while Bill and Susan shook hands.

As for the acutely hectic situation compelling him to seriously consider representation: Vollman’s UK publisher of the past decade (the main one, at least) was Andre Deutsch; a prestigious house for nearly fifty years, picking out and publicizing generational stars like Margaret Atwood and Philip Roth, Deutsch was fading with its namesake. In 2000 it would be folded into Carleton Books and cease to exist — dragging a good chunk of Vollmann’s catalog into a snare of questions: which licenses were expiring, whether to renew or revert, renegotiating…

“That’s when everything got more complicated for Bill,” she explained, “because for a little while he had three publishers: he had Grove, FSG [Farrar, Straus and Giroux] and Viking, and he would kind of play them off each other. He was a pretty good agent for himself.”

“I think I warned Susan that Bill is an interesting and unusual guy,” Franzen remembers in an email, “with an interesting approach to women,” one that — consulting the interview record — seems to manifest, partly, in telling them that they’re beautiful. You can hear him saying it to a waitress during a restaurant interview for The Bat Segundo Show.

In a 2014 profile for The New Republic: “The afternoon before, at lunch, Vollmann told our waitress he had a question: ‘How did you get so darn beautiful?’”

Or more strikingly in Madison Smartt Bell’s profile of Vollmann, in the New York Times Magazine (also 1996), where he watches as Vollmann tells a bartender she’s beautiful, and then asks if he can draw her. The bartender says fine.

“Vollmann is pleased,” Bell reports, “with a chance to try out a new mechanical pencil he bought this afternoon.”

The author doodles, finishes, slides it over — she loves it! Buys a round of drinks for him and his friends. Vollmann asks her what she would be drinking, if she were to join them, and when she says a Rémy Martin, he drinks that himself.

The “weirdness” thing comes up a lot, but the impression seems to fade before long. To the extent I’ve noticed a gender divide in the attitudes of people who know Vollmann personally, as I’ve conducted interviews for this piece and read the voluminous transcripts of others, it’s been men attesting that he’s smart, stubborn, strange, ambitious; women uniformly that he’s kind.

As far as firsthand accounts go, Vollmann neither drew nor said anything untoward when meeting Golomb. “I just remember Bill writing me afterward,” she said, “asking if I would take him on.”

This was her eighth year under the shingle of Susan Golomb Literary Agency, and four years after Franzen hopped aboard with his second novel Strong Motion. It was a small operation: just herself, a handful of clients, “one intern or maybe a part time assistant.” It wasn’t the right time to tackle something like Vollmann’s situation until a couple years later, 1998 or 1999. The first of his books that she sold was The Royal Family, which she describes as a normal sale. “Long book, but a normal sale.”

Vollmann hasn’t had one of those in a while.

William Vollmann has been interviewed by Michael Silverblatt, host of KCRW’s Bookworm, nine times since 1991, when he was touring The Ice-Shirt. Their conversations are warm, familiar, digressive, cerebral and increasingly playful over the years.

In the summer of 2024, I left a message on Vollmann’s voicemail saying I’d been commissioned to write a “tribute” for Silverblatt, who’d recently retired. I was wondering if I could get a quote.

Vollmann called back on a rainy afternoon, “Hi,” chipper as ever, “this is Bill Vollmann.”

I asked if he had a quote in mind for the tribute piece.

“Ozure!”

I got my hands over the keyboard. “Go ahead.”

What I respected most about Michael was that he respected the book more than he respected the author and he was not interested in doing puff pieces. If he didn’t like a book, he couldn’t be bothered. That’s very, very refreshing. So often [in an interview] it’ll be, “Well, Mr. Vollmann, I haven’t had time to read your book, and we only have five minutes, so could you tell us what questions to ask?” And I’m not averse to that. An honest hack like that deserves an honest prostitute like me. But Michael isn’t like that. He cares about the books. He asks some really good questions. I find probably the journalists who ask the best questions for the most part are the Germans. There’s also a little bit of schadenfreude. They hope to trip you up. But when it’s clear that I’ve done my homework, [and that I] remember what I write, it’s really interesting to get into abstractions and minutiae and so forth. American journalists are not that way. But Michael is somewhat that way. So it’s a pleasure to talk about my books with him. I consider him a friend.

So that last contract with Viking was initially challenged when the first of its three books was split into two volumes, released separately. Slovak, Vollmann’s editor, thought a single volume would have made a stronger argument; Golomb, his agent, thought the two volumes should at least have been shrink-wrapped into a single unit.

The next conflict came when Vollmann submitted the second title (technically the third book in what was now a four-book deal), The Lucky Star, which at the time it showed up in Viking’s mailbox still wore its working title, The Lesbian.

When you can see that something won’t be well-received, I asked Golomb, do you bring it up with him in advance, or just let it play out?

“Just let it play out.”

The Lesbian’s setup is almost a thought experiment: what would happen if Jesus Christ were here, in modern America, as a beautiful young pansexual witch in a Sacramento dive bar?

Vollmann’s answer is strangely persuasive. All of the sad lonely regulars would become her apostles, vying for her love, ultimately realizing she’s too large for their lives and deciding, as she fades away to fulfill her destiny, that the closest approximation they’ll ever find is if they love and care for each other.

Vollmann sees it as perhaps his darkest book, but it’s one of his most tender works as well.

Viking’s response was firm: This title has to go.

Vollmann was bothered — but mindful, still, of the concessions they’d made for Carbon Ideologies, the whole team of people who worked overtime, who took it on as basically a passion project, beyond the scope of professional duty. He writes in the novel’s Afterword about giving in, and changing its title.

This little defeat is unimportant to anyone but me. Or is it? Why was Viking so insistent? Why should it be unacceptable for me to publish a book with the word “lesbian” in the title? Would I have gotten away with it had I been born with different equipment between my legs? What does my surrender say about our time? What will be forbidden next?

He took it personally, not on the grounds of cultural sensitivity (though both Slovak and Golomb, looking back, remember 2019 as a peak moment in the discourse of who has permission to tell which stories) but a verdict about what he, as an author, was allowed to say. He was staunch in his defense that the title was not pejorative but ironic: it’s describing somebody who isn’t a lesbian, somebody who (like the almost entirely LGBT cast) is suffering because they don’t fit any of society’s labels. The pushback seemed to imply an accusation of some deeper prejudice — a judgement not only of him, but the novel.

Slovak is ready to grant that Viking’s resistance against this title was everything Vollmann says: a little bit personal, a little bit political, poorly presented — but he posits a way-simpler argument that Vollmann, in his interviews and Afterword, doesn’t entertain: The Lesbian “just wasn't a strong title. We wanted something poetic, metaphorical.”

When Vollmann gave in and Viking asked him to provide some alternative titles, he came up with four. One of them was Better Than Life. From the four, he chose The Lucky Star.

Paul, I did it for you. (Now I’ve come around to liking The Lucky Star. I can even tell myself I picked it.) But maybe, just maybe, I did it after inhaling a whiff of herd-fear, which weakened me. That is why whenever The Lucky Star meets my eye I am going to feel sad and, what is worse, ashamed.

Two titles into a three-title contract, both parties now had occasion to feel that the other had exploited their goodwill.

Jason Jefferies’s podcasting voice sounds like a crosslegged thing on a rug somewhere, his hair casually hooked behind his ear. He’s got a map of questions for the interviews he conducts on his podcast Bookin’ but he’s happy to digress: a good strategy with Vollmann.

“I think he regrets changing [The Lesbian’s] title, for sure,” said Jefferies, in a chat about his ten-year friendship with Vollmann. “I think he decided to do it because it’s the one concession he ever made with [Viking]. But knowing what I know about him, and how all of his other books got published, I cannot imagine him ever agreeing to change a title.”

When Jefferies last sat for an interview with Vollmann on his Bookin’ podcast, in 2023, it was over the phone. Vollmann wasn’t doing well. It had been only a year since Lisa died and he hadn’t traveled in a while. He had a new book to promote, which normally called for some travel and readings, but this new one hardly seemed worth the effort.

The latest release, a side project from the books he was producing for Viking, turned into its own scandal. A two-volume anthology, Shadows of Love, Shadows of Loneliness (one volume collecting his photography, the other his paintings) was a joint venture between two small publishers. They took payment from readers in 2020 but the books weren’t sent out to buyers until two years later.

When Rothacker reached out (as a customer, not Vollmann’s assistant) to ask what was taking so long, he was told — as were a few other buyers — that the shipments were being held up because of Lisa Vollmann’s death. The author, they claimed, was grieving, and slow in fulfilling his end of the arrangement.

Neither publisher responded to interview requests, but if you ask Vollmann what happened he’ll blame it on “incompetence.” It’s a strangely vehement thing to hear from Vollmann, spoken in the usual lilty, affable monotone. On several podcast appearances he condemns as “vile” the publishers’ remarks about his paralyzing grief over Lisa, the way they shirk accountability for the delay. Also, hey, open your text to pages X and Y and Z, where you’ll notice the photos are "unacceptably dark” or “washed out” and by the way he’s got some choice words for these publishers’ copyediting process, too, and one of those words is “nightmare,” because what would happen over and over is he’d find a bunch of errors in the text, send it back for corrections, and then when he received the new draft, OK, great, all those errors were fixed, except now there’s new errors peppered throughout, so what was the point?

On review aggregators like Goodreads, and Amazon, reader reviews for both volumes average between 4 and 5 stars.

Vollmann allows, in the Harper’s piece, that his emotions in 2023 were not at their usual level.

In each of these interviews, once he’s finished his Apology to the Reader, Vollmann clearly relishes a chance to talk about photography. He seldom gets a chance to do so.

Except for one particular instance, eerily, during an NPR interview in July 2014: he’s in the studio for All Things Considered, promoting his collection Last Stories and Other Stories, when his interviewer starts to dwell on one particular episode, called “When We Were Seventeen,” in which a widower’s struggle with cancer is so poignantly rendered, the host asks, “Were you sick at the time? Had you been sick?” A strangely pointed question.

But Vollmann’s answer is pat.

VOLLMANN: [In] the last few years sometimes, when I’m working with various difficult chemicals [in the darkroom], I might get a stomachache. So I thought, “Well, if I got stomach cancer, it would probably be like [this stomachache], only worse. So let me take some notes right now on my stomachache,” which I did.

INTERVIEWER: But you yourself have not been sick…This [depiction of cancer] was not a personal experience, only [made up].

VOLLMANN: That’s all it was.

Vollmann’s cancer was in remission in 2019 when he made it out to Raleigh, NC to sit with Jason Jefferies for an interview about Carbon Ideologies on Bookin’.

Jason first met Vollmann as an organizer for a local book fair, where he brought Vollmann along as a guest to discuss Last Stories and Other Stories. They stayed in touch and, over the next couple years, became friends. In 2019, apart from his roles as host and interviewer, he was taking Vollmann around as tour guide as well.

Vollmann looked different. Slim, a little more pensive maybe, jostling in the passenger seat and burping with acid reflux, excusing himself the whole way. He couldn’t eat fried or fatty foods, “he might have been on a vegetarian diet too,” and voiced some remorse at avoiding barbeque.

Lisa was still alive, but Bill was already voicing concern about her.

When she died, some of the people in Vollmann’s orbit didn’t know, or didn’t think he was grieving so heavily as he was, given the production of Shadows of Love, Shadows of Loneliness, and word about A Table for Fortune making its way through Viking.

But as Jefferies points out, those books were already done, and Vollmann was “definitely grieving.”

“Getting A Table for Fortune published was small potatoes compared to other things he was going through.”

“He didn’t travel for a while.” Jefferies says this with a pointed inflection, as though a Vollmann that isn’t traveling is an ailing one. “He is [traveling] again now,” he says, citing Vollmann’s trip, in the spring of 2024, to Ukraine, “but [in 2023] he wasn’t even going into his office. If I wanted to call, I had to call at his house.”

“And then he got hit by a car.”

Vollmann had touched on this in his TrueAnon appearance, apologizing to his hosts for having a runny nose (“It’s these opioids,” he explains over whisky).

“He saw someone breaking into the roof of his office and he tried to run across a busy street to [intervene],” said Jefferies. “Then a car hit him and he went through the windshield.”

And the phone calls? I asked. What were they like, when you reached him at the house? What would he talk about?

Jefferies paused. He said, “He talked about getting hit by a car.”

In recent interviews, when asked what he’s working on, Vollmann mentions only some nonfiction. Literary stuff comparing Melville and Lovecraft. A piece about Ayn Rand. Normally he talks about a novel or two, some short stories, an article on deck, some art books or a photo project...

If you’ve been following his career for a while it sounds like the first time he’s standing still, focused on just the one task before him.

In researching this piece, reading his interviews and reporting from the past couple decades, one thing that seems planted and constant amid all the locations, the topics, the books is his daughter Lisa. The static thing that anchors Vollmann’s blur. In recordings and prose and phone calls he talks about her birth and how, when he saw those med students testing his newborn’s reflexes by poking her all over, it was all he could do to keep from strangling them. How strange it was to feel that primal protective reflex. In a profile from twenty years ago a journalist visits the house and there’s Lisa, five years old, hopping over furniture. His friend Ken Jones calls the studio and hears a laughing ruckus and Bill’s on the phone saying, Oh that’s Lisa. She’s twelve years old in Carbon Ideologies, backing away from one of her dad’s friend who’s brought some (very slightly!) irradiated materials to the house. Later as a teenager she sees where her father’s FBI report makes a fuss of his acne scars and she’s telling him, “Poor Dad! I don’t think your face is pockmarked at all.”

Vollmann and his kid getting rose milkshakes in Dubai and he calls her his joy.

He shows her his crossdressing photos in The Book of Dolores and she loves it. He’s telling an interviewer that nothing in his life has so matured him as parenthood and he’s telling another that his daughter’s getting older and that he’s lucky they’re still so close.

That he tore his heart out trying to help her. That this anthology of his artwork was supposed to be finished in 2020, and it would have meant a lot to his daughter if she could have seen it, but the publishers were three years late, and now she can’t. He’s telling another how all the world’s beauty feels like bubbles now. Fragile.

That he’s getting old and his health isn’t great. That it’s harder and harder to do things but, hey, he doesn’t have to do much anymore. The only reason he worked so hard was for Lisa. To protect and care for her. “She’s as safe as she’ll ever be.”

There’s that piece from 1996 with the bartender who loves how he’s drawn her. Bill with his smile and his new mechanical pencil, so pleased to have pleased.

He asks if she’ll join him, but she can’t.

Alexander Sorondo lives in Miami. He's the author of a Substack newsletter,

, and his debut novel, Cubafruit, was released this year.

Staggering. This delicately and relentlessly reported piece just stunned me.

Another brilliant read.

What a life. 😳

When people ask me about the world of “Publishing” I feel like such a dilettante giving any answer— writers like Vollman are so prolific. He’s so wildly skilled at his craft, and yet the publisher/writer relationship is such a consequential piece of the puzzle. So many things have to go right at the same time for things to work.