One of the chief pleasures of Moshe Zvi Marvit’s sweeping family saga Nothing Vast is the way it transports you to places and times that feel soothingly distant from here and now. His characters move from Morocco and Poland to France, America, and Israel, and we meet them at various times between 1932 and 1973. Here is the sweet, foamy tea of 1935 Casablanca, poured from high above the table to keep the sand out; there, the “grimy” port city of 1956 Marseille and the boiling America of 1965, where “workers were rising up against fat business owners called pigs and taking over the factories.” Being immersed in these worlds and periods, however turbulent, is a pleasure, even though part of the point is that they aren’t really so distant after all. As Faulkner might have put it, the past of a family or nation is never dead; it’s not even past.

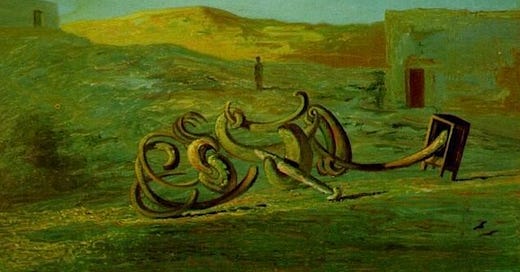

That is especially true of immigrant families, whose members must undergo the painful process of forsaking the lives they once knew and inventing new identities to graft onto the old. Marvit was born in Houston, Texas, and his European, Arab, Israeli, American, and Jewish heritage inspired the characters in this book. He reimagines his relatives’ various emotional and physical journeys with sensitivity and compassion. Nothing Vast evokes a Magic Eye image or a message written in invisible ink: now you see it, now you don’t. The characters are at once ordinary and remarkable; to many readers, they will be eerily familiar. Being pulled into their stories is startling and wondrous, like being visited by a long-lost relative.

The title is taken from a line in Sophocles’ tragedy Antigone: “Nothing vast enters the world of mortals without a curse.” To a character alternately called Misha and Oojie, this means that nothing is simple or painless, human beings are fallible, and there are ghosts everywhere. Several characters have multiple names, and most speak multiple languages. Marvit is interested in the multitudes we contain and the masks we wear: how and why we accept, reject, or alter the names that others give us and share different sides of ourselves with different people. These decisions are driven by impulse, instinct, and desire to claim or conceal our countries and families of origin. Sometimes we must hide parts of ourselves to survive, and speech can entrap or set us free. “French was a minefield like no other, everything a shibboleth, and everyone’s ear a trap in waiting,” Marvit writes in a section set in Paris in 1942. “A mispronounced syllable, an archaic or too-formal word, an errant idiomatic expression could give you away in an instant.”

Like speech, language can be used to oppress, humiliate, create closeness, or maintain distance. It can also allow for reinvention. And Marvit’s characters are constantly reinventing themselves: moving from one country, one language, and one way of life to another. These disruptions sometimes stunt them, but they also provide opportunities for transformation and reclamation. Liebe/Lillian is a Polish immigrant living in Brooklyn in 1938. “Liebe left Poland at age twenty-four and traveled back in time, arriving at Ellis Island as seventeen-year-old Lillian,” Marvit writes, adding, “Those years had been taken from her originally, so she felt no shame in stealing them back on the journey.” She could “be a different person here…since no one knew her, she was only the parts of Poland that she’d brought with her and held out for others to see.” At first Lillian prefers not to speak, as nothing good seems to come of it. “This was the rule that every immigrant knew,” writes Marvit. “As long as you kept your mouth shut, you could be anyone from anywhere.”

It’s not just individuals who reinvent themselves, but entire countries and peoples. Marvit has said that Israel is a character in this book; so are Jews as a people. He conveys what Israel, as an idea and a nation, means — both to the characters his family inspired and to Jews around the world — without ignoring the violence and dispossession that brought it into being. The book explores what happens when one group’s desire for refuge means obliterating another. As Marvit said in a recent interview, every place name in Israel represents “the ghost of a previous place and name.” Al-Khalil became Hebron, Ariha became Jericho, and so on. These ghosts live on; names can be changed and signs painted over, but the people who are driven out — and those who remain — remember what was.

The characters are vividly and memorably drawn, but the book shuffles among times, places, and perspectives so frequently that I sometimes wished we could stay in one place a little longer. Probably the people who inspired these characters felt the same. Marvit’s mother was a double émigrée who moved from Morocco to Israel as a child and from Israel to the U.S. in her early 20s. She “shut down” discussions of her or her family’s past, Marvit has said, lest excavating it should summon malignant spirits or invite the evil eye. His father’s parents came to America from Poland; his father’s mother, before the Holocaust, and his father’s father, after. They “could not bring themselves to talk of any past in any way.” Marvit hesitates to call the family stories that inspired Nothing Vast “history” since “so much of it exists in silences and contradictions.”

These silences and contradictions are present throughout the novel, which makes clear that what we don’t say is as important as what we do. A character called Miriam, though “usually a loud woman,” is a “master of silences;” when she is present but not speaking, “you could feel it more than words.” Marvit resists the temptation to lionize his forebears, even in fiction. His characters are complex but flawed, and he portrays them critically, with admiration and frustration. Rav Minsky wins the love of his community but fails to defend his daughter after another rabbi’s son attacks her. And he horrifies his grandson by ordering an Arab family off of what has become their land but was violently stolen from an Arab family in the first place. His fasting grandfather’s “hot, rancid breath” reminds the grandson that “even if Rav Minsky was a gaon [an outstanding Talmudic scholar] with an eye to the heavens, he was also an old man.”

“Trouble followed Jews,” a non-Jewish character thinks at one point, “it was a fact of history.” Nothing Vast grapples with this painful history and its effects across time, continents, and generations. As Jewish families around the world have seen, antisemitism is neither implacable nor inescapable. Marvit wrote the bulk of Nothing Vast between 2020 and 2022; in the acknowledgments, he writes that he “could not have imagined that it would be released as Israel was committing a genocide,” adding, “I condemn the genocide and continued occupation, and stand in solidarity with Palestinians in their continued struggle for freedom, dignity, and equality.”

Particularly after October 7th, some American and Israeli Jews have revealed how little they can see beyond their own families’ stories. But Marvit refuses to use even legitimate pain, fear, and love of a place to justify the oppression of others. Comparing Jewish suffering to that of the Arab family he has driven off the land, Rav Minsky tells his grandson, “Our tragedy goes back thousands of years. Our tragedy is deeper than theirs.” Nothing Vast shows why a person—or many people—might feel this way. And it shows where these feelings can lead.

Raina Lipsitz is the author of The Rise of a New Left. Her work has appeared in The Appeal, The Atlantic, The Nation, and The New Republic.

Suffering is not a contest. Yes, Jewish people like myself have endured prejudice and violence for thousands of years but so have others. Unfortunately, the history of humans is rife with genocide, destruction of cultures, and cruelty to others.

Well as someone of Polish Jewish origin I can confirm that there are many other cultures that also believe they have a monopoly on suffering. I remember a conversation many years ago in communist Poland where I was trying to explain to a friend what was going on in Guatemala, the murder of thousands of peasants, he stopped me and exclaimed: That is Nothing, compared to what we have suffered in Poland! WWII was not long past and the isolation of Poland because of the communist state created an ignorance of events that were ongoing. The Russians carry a similar rubric about their suffering in the last war. All of this is a honest acknowledgment until it turns into a monopoly of suffering.